Chronic Pain

Pain is a key sensory system that warns us when we need to stop and take care of ourselves. It has considerable survival value, however when we’ve dealt with the situation, or the wound has healed, we’d rather the pain would subside, completely, as it’s now more of a distraction to the pursuit of our daily lives.

Pain perception and active coping involves specific brain areas. With neurofeedback we can train these areas for a more optimal approach. We take a holistic approach, stabilising the person’s sense of self and general cortical functional connectivity. Chronic pain usually presents with other comorbidities, such as sleep and motivation issues, and various forms of anxiety. Neurofeedback has been shown to be evidence-based and effective for many of these.

Chronic pain affects between 35-50% of the UK population, yet pain management is inadequate in 40-60% of cases.

Dealing with chronic pain has always been a challenge. Drugs and medication offer temporary reprieve; this often comes at the expense of side effects, and the risk of habituation or even addiction. Moreover, our brain might even become resistant to the dose and the pain continues, should we not use even more.

Furthermore, pain is subjective – it manifests itself in many facets, including emotions, fear, helplessness, and at the very least it’s a distraction. When it’s chronic, we may be able to mask its effects, but that’s not to say the sensation infiltrates our general conduct and behaviour, our interactions, our mental calm and decision making. Increased agitation will affect our sleep and demeanour.

Pain is a perception. We integrate sensory stimulus with information from previous experiences, including emotions, amount of attention, and expectations about the pain. This means that if we can target higher order processes that regulate how we manage this information assimilation, and reduce its sensitivity to manageable levels, we can potentially break the cycle. This is what neurofeedback aims at. Recent clinical outcomes indicate that the technique of EEG (brain wave) biofeedback can be used to break the cycle and lead to a major decrease or (more rarely) even the total elimination of chronic pain. Calming, both physical and emotional, is what neurofeedback aims at, and this can be a valuable intervention in the negative feedback cycle that is chronic pain.

Neurofeedback is not a substitute for finding the underlying cause of pain, which should be thoroughly investigated by medical means as a primary remedy.

Quick Navigation

Neurofeedback Process

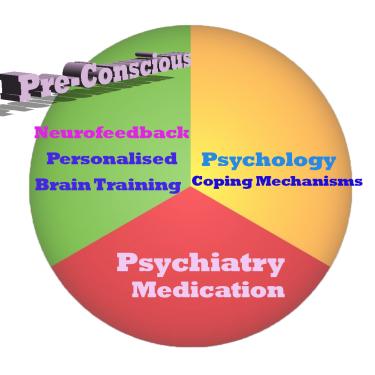

Our understanding of the world is governed by how our brain processes sensory information. Most of the sensory processing is preconscious, that is, before it reaches our conscious awareness. The more efficient these subconscious processes are, the more easily we can live in the moment and share a reality with others. Conversely, when sensory processing is inefficient, mental health issues can arise. A brain map lets us identify strengths and vulnerabilities.

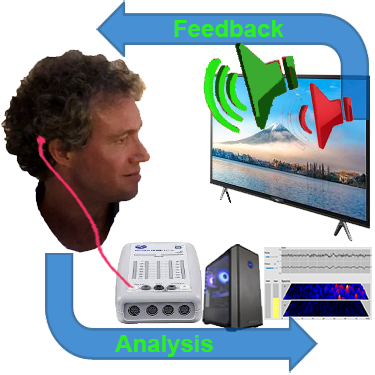

Neurofeedback lets us train dysrythmic brain areas. With sensors comfortably fitted to the brain areas we want to train, we detect brainwave patterns real-time while watching a movie. When these patterns are inefficient, the volume drops momentarily. This is the feedback we are giving our brain, short and instantaneously. The brain area we are training recognises this – while our conscious mind is focussed on the movie – and adjusts its behaviour to restore the normal volume. With repetition, throughout a session, learning occurs. Meanwhile our conscious mind is solely focussed on the movie; the training process is passive in this sense.

The drop in volume is subtle, so we continue to understand the flow of the movie. No current or electrical stimulation is fed to the brain; sensors simply read brainwaves and the feedback is purely audio-visual.

Neurofeedback is Evidence-Based

Chronic Pain patients experienced a 44% reduction in pain following neurofeedback.

Chemotherapy patients experienced a 45% reduction in pain, reporting a significant improvement in pain severity, numbness, fatigue and quality of life, with effects still upheld four months after neurofeedback treatment.

Fibromyalgia patients saw an 82% reduction of fatigue, depression and anxiety, and an increase in social and physical functioning; these effects were upheld. Another fibromyalgia study with different neurofeedback protocols achieved a 39% improvement, and another found a 55% improvement. Neurofeedback training improved functional connectivity in somatomotor areas leading to reduced impact of fibromyalgia and pain symptoms and improved quality of life.

Complex regional pain syndrome sufferers achieved a 42% reduction in pain, muscle spasm, muscle tension, and in increase in well-being.

Central Neuropathic Pain resulting from Chronic Spinal Cord Injury saw a clinically significant 33% reduction in pain, interestingly using home-based equipment. Central neuropathic pain has a 40% incidence in patients with spinal chord injury. Another study found a 30% reduction in pain with a concurrent “pleasant warmth replacing unpleasant sensations”.

Subjective pain perception was significantly reduced in acute whiplash patients in this study.

Case Study: Neurofeedback and Pain

Case examples from the EEGInfo Institute in Los Angeles demonstrate how neurofeedback can be effective:

“A case in point is “Ted” (not his real name), who was nearly electrocuted. Three years later he was still “…suicidal with agony.” He had been to a number of psychiatrists, and some of the

medications they provided helped for a while, but the pain always returned. In great desperation, he came in to have his pain sensitivity retrained with EEG biofeedback. After only a few sessions, his pain was reduced to where it no longer bothered him, and he returned to a normal life.

Another example is “Jack,” who came in with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, a kind of whole body pain, along with chronic fatigue syndrome. Within three weeks, he was free of what he described

as “bone-crushing pain” for the first time in six years. He went on and did a number of additional sessions of EEG biofeedback to consolidate his gains, but the major difference was made early on

One of the most gratifying examples of the power of EEG biofeedback to relieve pain was the case of “Doris,” who underwent hip-replacement surgery in April of 1996. After several months, the pain was still at “six” on a scale of 1-10 despite heavy medication, and she continued to require crutches to walk. She began a program of EEG biofeedback and within a month the pain had been reduced by half. By November she was no longer using crutches and began to be able to make dance movements, while having greatly reduced episodes of significant pain. As of the writing of this article, she is essentially pain-free, and only uses medication occasionally at night. Now she is even able to do a bit of running.”

Source: “New Hope for Sufferers of Chronic Pain” by Siegfried Othmer

Neurofeedback for Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia is often linked to trauma and presents with other symptoms such as anxiety, mood dysregulation and sleep issues. Neurofeedback is an evidence-based treatment for many of these comorbidities.

The elusive source of pain in fibromyalgia can result in misdiagnosis, and often skepticism from medical professionals, compounded by a lack of specific treatment options. This can further erode the sufferer’s self confidence, as they are faced with doubt and misunderstanding. With neurofeedback, we take a holistic approach by stabilising the Default Mode Network, thus re-establishing a healthy sense of self; helping with exacerbating factors such as sleep and motivation issues, and anxieties. Neurofeedback has been shown to be effective in trauma and PTSD.

Fibromyalgia patients report significantly improved pain severity and interference, fibromyalgia symptom severity, sleep latency and sustained attention following eight weeks of neurofeedback training.

A separate study finds significant improvement in cognitive dysfunction, fatigue, pain, sleep, depression and overall activity level in fibromyalgia sufferers, further illustrating the debilitating comorbidities of this condition.

Fibromyalgia patients saw an 82% reduction of fatigue, depression and anxiety, and an increase in social and physical functioning; these effects were upheld. Another fibromyalgia study with different neurofeedback protocols achieved a 39% improvement, and another found a 55% improvement. Neurofeedback training improved functional connectivity in somatomotor areas leading to reduced impact of fibromyalgia and pain symptoms and improved quality of life.

Chronic pain sufferers of Spinal Chord Injury found immediate and lasting effects on pain intensity from neurofeedback training.

Various Forms of Anxiety

There are multiple types of anxiety, each correlating with one or more brain areas being dysrhythmic:

When we’re in a situation with other people and our understanding of the social dynamics and complexities is overwhelmed.

Hypervigilance as a result of avoiding a bully or abuser is another form of anxiety. We can detect vulnerability to this with a brain map.

Our brain interprets all sensory stimulus as directed to ourselves. We lose the ability to discern what is directed at us, and which matters or interactions are of no concern to us. This sets us up for panic attacks and ultimately psychosis. It also means we become singular in our perspective, unable to take on other points of view.

An extreme example is when we feel that too much is going on around us and we respond by having to turn the music down, explode at our environment or, potentially worse, retreating into tacit acceptance and self-deprecating thought. We can even feel that people are talking about us, and are convinced that we are the centre of every situation. This is highly stressful, resulting in anxiety and often deep depression. With neurofeedback, we can restore the brain’s ability to self-regulate efficiently.

Our episodic understanding of the situation, how we got there and what happens next, is impaired, and we are unsure of where we are and where we’re going. This hyperactivates our amygdala, and the sensation is highly emotional

We become prone to overly interpreting the emotional content of words and sounds, creating an air of prickliness and pushing people away without knowing it

Our Ascending Reticular Activating System (ARAS) is responsible for setting the right level of physiological arousal, or wakefulness, for the situation, and to remain stable there. When this is on overdrive, we are pushed further into fight-or-flight mode than necessary, thus heightening sensory sensitivity. Panic attacks are an extreme manifestation. We may also feel trauma-like body sensations.

An inability to self-nurture – creating an emotional safe-space around us – and self-soothe – being able to talk ourselves down rationally from a situation, thus resulting in mood instability. This can also manifest in dissociation and heightened pain perception, fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue. We ruminate about the past and worry about the future, instead of being able to enjoy the present.

Our autonomic nervous system is primed to produce sympathetic nervous system responses, or fight-flight-freeze mode. This wears us down, as it is more energy intensive, our recuperation periods are shortened and we can even become used to the adrenalinergic buzz of being in hypervigilant overdrive. It becomes a safe space. Our pain perception is altered and fluctuates between numbness and hypersensitivity. Deprived of a ‘calm’ reference state, we become vulnerable to overattributing emotions to sensations.

Dissociation is another phenomenon that can ensue, and this can be subtle and paroxysmal. Engagement of defensive mechanisms is triggered pre-, or subconsciously. This can compromise our ability to rationally self-soothe – the role of our prefrontal cortex. Instead, our limbic system is primed. We also lose our emotional sense of safety. The integrity of our Default Mode Network is challenged, as is the natural transition between its activation and that of the Task Positive Network. We are less able to regulate engagement with our environment and the neurological basis for our sense of self is under threat.

There are distinct brain areas regulating pain, physical sensations and our self-awareness, and we can train these with neurofeedback. We can also train brain areas with strong connections to sub-cortical structures that regulate our autonomic nervous system, including the amygdala and our reticular activating (or limbic) system. Our brain is ultimately in charge of trauma response, and with neurofeedback we can assess vulnerability to its various submodalities, and address these with training. This is evidence-based and effective.

Self-criticism overshadows motivation and confidence, and we become self-aware and distracted by negative thoughts and feelings. Some use acquired habits to distract from this. Our confidence, motivation and social interaction suffer as a result.

Over-attentive with regard to bodies, shapes and faces, and excessive monitoring of our own in relation to others, our self-confidence and social interactions suffer. There are neural correlates for this which we can train.

Sleep is adversely affected by trauma and anxiety. First, the mind needs to ‘let go’ in order to enter deeper sleep cycles, which is a challenge for many. Excessive rumination and intrusive thoughts can hinder this, as does the loss of our ability to rationally calm ourselves down. The depth of our sleep is governed by our ability to self-nurture and create an emotional ‘safe space’. Homeostasis during various sleep stages is governed by other parts of our brain, some still involving the cortex. With a Kaiser Neuromap we can detect dysrhythmia in the relevant brain areas and train these accordingly with Default Network Training (together, Personalised Brain Training).

Focus and organisation suffers as a consequence of sleep issues. This time, different brain areas are affected, which we can also train. When we are unable to concentrate and produce our best output, we become demotivated and our mood and sense of self suffer. Again, there are brain areas responsible for these aspects of being, for which we can again detect dysrhythmia and provide neurofeedback training. The process is holistic – many components have to work together effectively for us to function optimally.

Mood regulation suffers when we lose social integration, sleep and focus. Neurofeedback training found to significantly help 80% of people with depression by aiming to restore motivation, improving sleep and focus, and reducing anxiety.

There are numerous potential cortical contributors to depression, and with a brain map we can see vulnerabilities.

Neurofeedback training lets us address these as well as establish a generally improved sense of well-being in a holistic manner. The positive effects of neurofeedback training have been shown to be lasting. Neurofeedback is non-invasive and medication-free.

![ARAS Ascending Reticular Activating System and performance curve with different levels of physiological arousal; we can train our ability to find and be stable at the optimum level of physiological arousal with neurofeedback training]](https://neurofeedback.io/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/ARAS-for-Website.png)

Sleep

"I felt so calm last night! And slept like there were magnets between me and the bed. 10 hours straight."

"Slept like a log."

"Since I started neurofeedback training, my dreams have come back!"

Client testimony.

Sleep is where we recover – physically, mentally, emotionally.

It is a complex process whereby the brain enters different behaviour patterns in various stages. Slow wave sleep is where our body recovers; REM sleep is where we digest the day’s experiences, consolidate what we’ve learned and let our brain process memories and impressions.

Ideally, we would like to be able to switch off once comfortable, enter a deep sleep and wake up restored and energetic. If our sleep suffers, so do our concentration, productivity, physical abilities and emotional flexibility.

Neurofeedback has also been successful in treating other sleep disorders, such as somnambulism (sleepwalking), obstructive sleep apnea (to the extent the cause is not physical), confusional arousals, sleep terrors, nightmares, nocturnal enuresis (bed-wetting), delated sleep phase disorder, insomnia and restless leg syndrome. Evidence is provided at practitioners’ conferences and has yet to be manifested in published research. The above disorders have EEG correlates, which provides an intuitive basis for understanding that we have a chance at treatment with neurofeedback training.

Different neural hubs are responsible for sleep onset and depth of sleep. We can identify vulnerabilities with a brain map, and train these with neurofeedback to help restore healthy sleep hygiene.

Sleep is usually one of the first things to normalise during neurofeedback training.

We have also seen improvements in other sleep conditions, such as enuresis and sleep apnea.

Trauma, Abuse, PTSD

Trauma and abuse leave scars.

When the viability of our existence has been subjected to threat, our behaviour adapts. We become primed for hypervigilance, sensitive to triggers, and our physiology responds accordingly. A heightened sense of awareness now confers safety, and we can even become addicted to this.

Our brain keeps the score: Areas responsible for defence and vigilance are activated, even when there is no objective reason. Sensory stimulus is amplified, and we dedicate value energy resources to the monitoring of others’ intentions. Anxieties are rekindled, and the strain on our system leaves us exhausted while unable to switch off and effectively recuperate. Our focus and productivity drop, as does our self-esteem. We can feel detached from our bodies, dissociating. Our social capacity is impaired.

Neurofeedback helps us break this cycle: we equip the brain to get over it, to get on with it, re-establish our sense of self-worth, and the ability to constructively engage with our environment. We gain a healthy sense of detachment, which allows us to process the past more efficiently and look forward to the future.

With a brain map, we can identify which parts of our system are being particularly stressed. Neurofeedback training helps us bring these brain areas into better alignment.

The first indication that we are experiencing trauma / PTSD is when we find ourselves not living in the present. Enjoyment of the moment and social interaction is clouded by constant ruminations about the past, and worries about the future. We are unable to ‘let go’, relax, and grasp opportunities as they present themselves in the Now.

We are plagued by intrusive thoughts that bring us back to events in the past, which needn’t even be related to a traumatic event, but which remind us of some inadequacy and amplify our self-doubt. Feelings of shame and guilt come into the picture as well, further eroding our self-confidence. “How can I be happy and enjoy this after what has happened?”. Similarly, our perception of the future is shrouded in worry and fearful anticipation. Uncertainty is our greatest foe, our perception of safety is unhinged by any doubt as to what could happen next.

The absence of a plan becomes a concern, the lack of clarity as to what’s around the corner a burden. Negativity associated with the past deprives us of hope. We are thus unable to see uncharted territories ahead as an opportunity, and much rather dwell on impending threats.

Indeed, our system is primed to protect us, and we are in survival mode. This process becomes self-feeding as we become addicted to the hyper-arousal our sense of fear induces. Our sense of joy and looking forward to fun becomes clouded to the extent we forget and no longer yearn it. Detachment sets in, further isolating us from feelings that previously motivated us. This process can even start slow and subtly, yet the cycle is self-fulfilling and deprives us of the necessary perspective to break and get out.

In Personalised Brain Training, our definition of trauma is wider. We include for example perceived loss of social standing, which can be either the cause or the consequence of a traumatic event or development. The perceived loss of social position results in us feeling judged. We become hypersensitive to how people approach us, talk to us, deal with us.

This is a subjective concept, as it should be, given that trauma should be recognised as an issue of perception by the affected person, rather than a concept being ‘awarded’ by an unrelated party, though external affirmation can help and medical advice should be sought in any event. As humans, social recognition is a critical component of our biological drive to propagate. Attraction relies on this, which ultimately leads to bonding.

Consequently, there are numerous brain areas devoted to, or involved in, the assessment of our position with regard to others. When our self-perception is assailed, or even the viability of our self is questioned, we are naturally shaken. Various brain areas become dysrhythmic. These include areas responsible for our body control and awareness, and many therapies focus on engaging the body and somatosensory system with a view to inducing cerebral changes.

However, this is only a part of the picture – there are many, arguably more powerful neuronal centres in the brain that are affected by trauma, and with a Kaiser Neuromap and Default Network Training (together, Personalised Brain Training), we can assess the issues more accurately, completely and efficiently, as well as then successfully training the brain to overcome trauma and setting ourselves on course for a positive trajectory.

Another consequence of trauma is that we may feel unable to rationally assert a sense of safety. This is different to self-nurture, or an emotional sense of safety. When we are unable to talk ourselves down from a situation we lose the ability to effectively regulate our moods, to switch off when we need to, and ultimately can become excessively paranoid.

There are neural correlates for this behaviour, and we can asses this with a Kaiser Neuromap. Safety and assurance are core needs we are programmed to seek to fulfil. Authority and role models help us in this quest. When we become dysregulated in our ability to self-soothe, we are also compromised in our ability to find paternal guidance. As a result, we tend to over-idolise figures who seemingly exude strength and power, or disobey completely and become unnecessarily rebellious – both immature behaviour patterns. Resetting this balance is crucial to achieving calming, regulated emotions, reduced hypervigilance and controlling impulsiveness. Personalised Brain Training lets us achieve this.

When hypervigilance persists untreated, we face further problems.

Physically, our heart beats faster and harder, more of the time, which is a clear stress on our system.

Mentally, we become prone to developing intrusive thoughts, even when we are able to relax, and more so when we are stressed, where these can take on third-person character, a voice in our head. This can have a destabilising effect, not least because we are now spending energy ‘defeating’ other perspectives we are internally engaged with, and thus distracting us from the ‘now’. Being on hyper-alert can also make us more susceptible to feeling relational to sensory input, in that we feel that everything is directed at us, which can set us up for psychosis.

As we lose our ability to enjoy the moment, our social interactions suffer. Exercising our social brain keeps us alive and forms the basis for sound mental health. Our brains are adaptive, and we need to provide stimulus to maintain connections and sustain flexibility. Isolation deprives us of many necessary exercises. For example, brain areas that deal with face recognition also respond to affective interactions and the ability to discriminate between emotional content of faces. We need to keep training these brain areas through social interaction in order to maintain emotional recognition – it is not a surprise that perpetual mask-wearing heightens our social anxiety (aside from adverse physical effects).

Social recognition, a key component of our biological need to attract and bond, is driven by sensory interpretations. Again, we need to exercise brain areas that contribute to this, including language and speech generation and comprehension, auditory sensitivity, and monitoring rewards for actions, both directly and vicariously. Our mirror neuron system contributes towards learning from others’ mistakes or examples, and consequently the storage of social rules necessary for constructive functioning in a society.

Inclusion is imperative to establishing a healthy self-image or sense of self. This in turn is crucial to forming stable relationships with friends, family and forming healthy alliances necessary for personal and professional progression. When we lose our sense of belonging to a group or cause, we may become unstable in our self-perception and our relationships with others. The effect may snowball into perceptions of abandonment, feelings of emptiness and dissociation; this in turn correlates with mood dysregulation, impulsive and often dangerous behaviours, intrusive thoughts and potential self-harm.

With Personalised Brain Training, we can assess vulnerability to these traits as they manifest in functional brain area dysrhythmia that shows in a Kaiser Neuromap; with Default Network Training, an advanced form of neurofeedback, we can train these brain areas and networks in a holistic manner to help re-establish balance. This enables us to reconnect with our environment and re-enter a positive feedback loop.

Sleep is adversely affected by trauma. First, the mind needs to ‘let go’ in order to enter deeper sleep cycles, which is a challenge for many. Excessive rumination and intrusive thoughts can hinder this, as does the loss of our ability to rationally calm ourselves down. The depth of our sleep is governed by our ability to self-nurture and create an emotional ‘safe space’. Homeostasis during various sleep stages is governed by other parts of our brain, some still involving the cortex. With a Kaiser Neuromap we can detect dysrhythmia in the relevant brain areas and train these accordingly with Default Network Training (together, Personalised Brain Training).

Focus and organisation suffers as a consequence of sleep issues. This time, different brain areas are affected, which we can also train. When we are unable to concentrate and produce our best output, we become demotivated and our mood and sense of self suffer. Again, there are brain areas responsible for these aspects of being, for which we can again detect dysrhythmia and provide neurofeedback training. The process is holistic – many components have to work together effectively for us to function optimally.

Mood regulation suffers when we lose social integration, sleep and focus. Neurofeedback training found to significantly help 80% of people with depression by aiming to restore motivation, improving sleep and focus, and reducing anxiety.

There are numerous potential cortical contributors to depression, and with a brain map we can see vulnerabilities.

Neurofeedback training lets us address these as well as establish a generally improved sense of well-being in a holistic manner. he positive effects of neurofeedback training have been shown to be lasting. Neurofeedback is non-invasive and medication-free.

There are multiple types of anxiety, each correlating with one or more brain areas being dysrhythmic:

- Social anxiety: When we’re in a situation with other people and our understanding of the social dynamics and complexities is overwhelmed.

- Sensory overload: our brain interprets all sensory stimulus as directed to ourselves. We lose the ability to discern what is directed at us, and which matters or interactions are of no concern to us. This sets us up for panic attacks and ultimately psychosis. It also means we become singular in our perspective, unable to take on other points of view

- Loss of narrative: Our episodic understanding of the situation, how we got there and what happens next, is impaired, and we are unsure of where we are and where we’re going. This hyperactivates our amygdala, and the sensation is highly emotional

- Auditory sensitivity: we become prone to overly interpreting the emotional content of words and sounds, creating an air of prickliness and pushing people away without knowing it

- Activation: Our ARAS is responsible for setting the right level of physiological arousal, or wakefulness, for the situation, and to remain stable there. When this is on overdrive, we are pushed further into fight-or-flight mode than necessary, thus heightening sensory sensitivity. Panic attacks are an extreme manifestation.

- Trauma: an inability to self-nurture – creating an emotional safe-space around us – and self-soothe – being able to talk ourselves down rationally from a situation, thus resulting in mood instability. This can also manifest in dissociation and heightened pain perception. We ruminate about the past and worry about the future, instead of being able to enjoy the present.

Intrusive thoughts: Self-criticism overshadows motivation and confidence, and we become self-aware and distracted by negative thoughts and feelings. Some use acquired habits to distract from this. Our confidence, motivation and social interaction suffer as a result.

Anxiety results from hypervigilance and indeed this cycle feeds itself. There are numerous forms and sources of anxiety, which are visible on a Kaiser Neuromap.

With Default Network Training we can achieve calming, and furthermore assist change in functional connectivity of brain circuits that keep us in a primed, anxious state.

The primary issue of trauma affects brain areas that are activated during empathy and forgiveness. With these two qualities impaired, our emotional life suffers, as do our social capacities. With neurofeedback training, we can restore functionality of these brain areas. Another reason this is important is because we do not want to become oppressors ourselves. As we lose our sense of emotional investment in our surroundings, we become careless with regard to others’ feelings and needs.

Implicitly, we are now capable of unintended yet real behaviour patterns that can harm others, as we become deaf to feedback. Not only has trauma affected us, it now makes us perpetrators that pass it on.

Besides reduced social interaction and a less meaningful emotional life that is now more self-centred – and with the wrong type of therapy, becomes self-indulgent and self-perpetuating – we can experience a physical withdrawal from our environment. Dissociation can be momentary and intense, or subtle and ongoing to the extent that we are not even cognisant of it. Either way, our bodies retreat from sensations, analogous to our emotional withdrawal.

Many therapies aim to revive our sense of ownership of our bodies, and thus ultimately our life and future, by training our body awareness in various ways. Realising that our bodies are steered by our mind, specifically our cortex, we can train the relevant brain areas that govern our body perception and movement execution.

Neurofeedback training effectively complements these approaches by directly treating the areas involved in perception and interaction with our surroundings.

One of the first manifestations of trauma is in our bodies. Aside from heightened physiological arousal, a form of paralysis can override our natural motions and postures. Stress, and pain ensue, which can often be felt all around the body. Fibromyalgia is a variant of this phenomenon, as are headaches, chest pains, and chronic fatigue.

There are many techniques for combating this form of physical dissociation. Neurofeedback complements these by training the brain areas that instruct the body to behave in this undesirable way. It is a holistic approach, and we restore overall calming while providing the brain with rational and emotional capacity to overcome its challenges.

Neurofeedback is a form of complementary therapy and should not be seen as a replacement for conventional medicine. qEEG brain map-based neurofeedback training takes a more holistic approach to brain functioning, rather than just focusing on medical symptoms. It is not intended as a form of diagnosis nor medical intervention nor medical advice per the disclaimer.

Brain Maps and Personalised Brain Training Explained

Personalised Brain Training with Neurofeedback

Neurofeedback lets us train dysrythmic brain areas. With sensors comfortably fitted to the brain areas we want to train, we detect brainwave patterns real-time while watching a movie. When these patterns are inefficient, the volume drops momentarily. This is the feedback we are giving our brain, short and instantaneously.

The brain area we are training recognises this – while our conscious mind is focussed on the movie – and adjusts its behaviour to restore the normal volume. With repetition, throughout a session, learning occurs.

Meanwhile our conscious mind is solely focussed on the movie; the training process is passive in this sense.

The drop in volume is subtle, so we continue to understand the flow of the movie. No current or electrical stimulation is fed to the brain; sensors simply read brainwaves and the feedback is purely audio-visual.

Neurofeedback trains our Pre-Conscious Mind

Rather than engaging the conscious mind, which slows us down, we are training preconscious processes.

This equips us with the ability to live in the moment and attain our potential (if we have to resort to conscious control, we are not living in the moment).

We take a holistic approach to healthy brain self-regulation, rather than categorisation or diagnosis.

Personalised Brain Training is an advanced qEEG brain map-based approach to neurofeedback training developed by the founders of the field. Taking Othmer Method / ILF training methods further, it employs Default Network Training protocols as developed by David Kaiser.

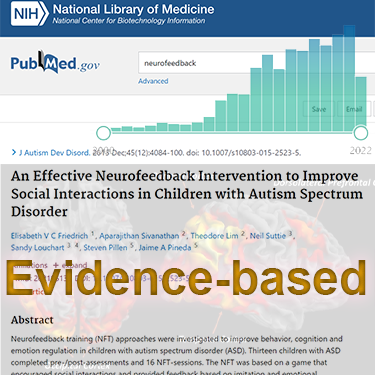

Neurofeedback is Evidence-based

Neurofeedback training is an evidence-based complementary therapy. Its efficacy was first demonstrated some 50 years ago, and with advances in technology, training protocols have become more efficient and the feedback method – watching movies – thoroughly enjoyable.

Neurofeedback is evidence-based. It’s first application was discovered in 1971 when it was used to resolve intractable epilepsy.

There are over 2,000 peer-reviewed research reports on PubMed demonstrating efficacy across a number of pathologies.

In the US, it is an accepted complementary treatment for many challenges.

The Process Explained

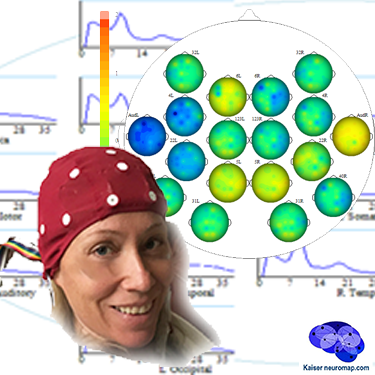

Step 1: Brain Map

A qEEG recording takes about 45minutes for a 20 minute recording.

A cap with 19 sensors is is fitted to our head and gels inserted to ensure connectivity. The sensors only read – there is a tiny voltage on the surface of our head that these pick up. The gels are easily washed out later. This is also the last time we wear the cap (until a remap after ten sessions); training is done with single sensors.

We analyse the data with Kaiser Neuromap software which gives us a unique view into character traits and vulnerabilities.

Findings are presented in a separate one-hour conversation where we discuss the key elements.

Step 2: Neurofeedback

We use a movie of choice as the feedback mechanism – our conscious mind engages with the film, and feedback is delivered by small changes in volume or picture size.

Our pre-conscious mind adapts its behaviour to preserve the more comfortable volume and picture size, and learning occurs.

Volume changes are slight, not stop-start, and the process is enjoyable.

Key is that we are interested in the movie – our conscious mind is engaged with the content, which forms the reward, and our preconscious mind – without our conscious effort – changes its behaviour in response to the feedback.

A two hour training session allows us to do 90-110 minutes of neurofeedback training during which we can work on various brain sites.

This captures an entire ultradian rhythm cycle and corresponds to the approximate duration of feature film movies.

We can start with shorter sessions as appropriate, mainly with children.

Ideally, we do two or more sessions per week to start with.

We would expect to see responsiveness within the first few sessions and remap after twenty hours or about ten sessions.

Generally, we would expect to doing twenty sessions over two months, though this can vary substantially.

We can also accommodate intensives, where we do two sessions per day over a number of days, and have had good results with these.