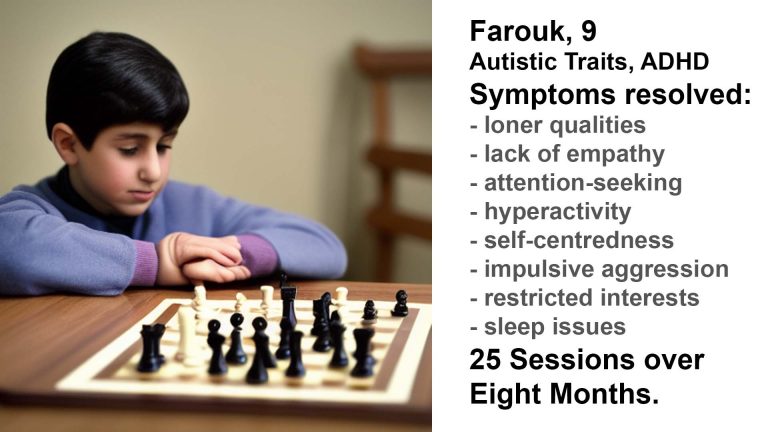

Case Study: Farouk, 9, Autistic Traits, ADHD

Social Interaction, Behaviour and Sleep Improved.

Before

Issues with:

– lack of empathy, understanding social emotions

– loner qualities

– attention seeking, “class clown” behaviour, hyperactive

– centre-of-the-universe thinking, self-centred

– inflexibility, impulsive aggression

– mild repetitive, restrictive behaviour and interests

– sleep issues – early rise, inadequate sleep time

25 Sessions over Eight Months

After

– calmer, considerate

– emotional maturation

– part of social circle, friends

– improved sleep and rest

– feels valued, appreciated

– flexible, stable moods, self-control

– widened interests

– better relationship with mother

Farouk's Full Story:

Farouk is 9 years old. Growing up perfectly bilingual, he is an outstanding academic performer, excellent at chess and mathematics, and attends a strict school with structured after-school activities. He was diagnosed with ADHD and some subclinical autistic traits, which stimulant medication exacerbated. Highly energetic, Farouk was difficult to manage in his home environment, and his mother had the following concerns that led her to seek a psychiatric assessment:

- Lack of empathy: Farouk would laugh at his schoolmates sufferings, such as when someone fell or hurt themselves, or performed badly. This made him appear cruel and indifferent at times, generating hostility at school and also at home with regard to his younger brother

- Loner qualities: Farouk found himself frequently ostracised as a result, and also didn’t seek out friendships and alliances at school by himself

- Inflexibility and impulsive aggression: Farouk consistently insisted on getting his own way, and when met with rational resistance, would persist out of apparent spite, unwilling to accept reason or engage in negotiation. This caused much friction at home, as everything had to revolve around him, and his energy and persistence would wear down his family members to the extent that they learned to acquiesce and accommodate him in every way, often to their own detriment. Farouk’s outbursts whenever he was confronted with any sign of resistance were compounded by his physicality, and induced weariness and hypervigilance in parents, while his younger brother was often not getting the attention he required. The family had even moved home to accommodate his desire for a bigger room. His mother felt unable to provide him with the requisite warmth and emotional support out of sheer exhaustion, which was a sensitive topic as she realised he felt underloved. The father was largely absent and concerned with his business, and Farouk was often left in his room under camera supervision.

- Attention seeking behaviour and hyperactivity: Farouk also excelled at individual sports such as swimming and karate, while showing no interest in team activities. His school was strict and structured, and he frequently received sanctions as a result of disruptive behaviour. He was also easily recruited into performing pranks to impress his schoolmates, leading to a suspension that compounded his adversarial outlook towards authority. Farouk often felt betrayed, and not part of a group or bigger cause. He became hypervigiliant and suspicious, and his moods fluctuated substantially

- Mild repetitive, restrictive behaviour and interests: Farouk could watch comedy cartoons for hours on end and was very hostile towards curtailment of his screentime. While his sports activities were varied and his intellectual capacity wide, he immersed himself into new passions with exclusive intensity; this included Transformers, the collection of which dominated his bedroom; and magic tricks (and pranks!) that he would perform to his parents’ and schoolmates’ exhaustion

- Sleep was an issue: Farouk would not get to sleep before 10pm, and was awake at first light, which could be very early in the summer months. Besides being inadequate rest for a 9 year-old, this also deprived the parents of their deserved recuperation.

When we began neurofeedback training at his home, his parents were wary of his willingness to cooperate, as well as the effect it could have, as they’d tried various approaches before, unsuccessfully, and were worn down by him to the extent it became a strain on their own relationship. Farouk entered the room with suspicion, and seeing that someone new was willing to give him attention, began showing me some magic tricks. We then suggested a brain map to him, and a knee-jerk reaction of “I’m not doing it!” quickly ceded to intrigue and interest. He quickly relented, having built up some trust, and also with the promise of a reward and the threat of sanctions by his mother. We did a twenty-minute qEEG recording, which confirmed the traits above. It was also apparent that he was not getting the necessary sleep, and as a result some intra-cortical communication was inconsistent.

Neurofeedback sessions with Farouk required special attention and presence: He was thrilled at the one-on-one attention of someone he could present his latest tricks and insights to, and once settled, had to check the workspace for pranks, such as magnets under the table on which the equipment was set up. We began with some youtube tricks, usually pranks, sports failures and cartoons, and he demanded my full attention to the content, which he would comment on. Vigorous, unexpected jerky movements commanded another eye on the equipment and cables, and demanded a calming, authoritative yet accommodating presence. We then eased into feature films, which he could watch for at most a half hour initially, losing interest in plot and character development. This improved with every session, and his immersion evolved quickly. Content had to be moderated to avoid repetition of a theme (Transformers) and over-activation, sometimes involving negotiation and distraction.

Still, we were able to do two-hour sessions that generally left him in a state of calm focus. His parents would structure physical activity around the sessions to prepare him beforehand, and deplete any remaining hyperactivity after. Strict adherence to mealtimes he was accustomed to had to be respected.

Within five sessions, Farouk became noticeable calmer in general. He began to develop an insight into some of his more adversarial behaviour, expressing feelings of guilt and remorse when he was reprimanded for attention-seeking pranks. He was sensitive to his mother’s admonishments, and she too was able to engage more emotionally with him. Sleep was still an issue.

We continued the weekly sessions, and for the next ten sessions, improvements seemed slow. A remap showed considerable changes however, in particular with regard to structural maturation as well as mood control. His parents were distracted by family and business matters, and his younger brother required more of their attention during this time.

A change in protocols prompted by the remap let us address other issues that are usually more tangentially related to sleep, but proved highly effective. Farouk began to accept that he needed more sleep and no longer resisted bedtime reminders and his habit of secretly reading and playing when the lights were turned off, as he admitted to his mother. He also ‘overslept’, in his own words, and it became a competition with his brother as to who could wake up later. This was a relative concept, as it still meant a 7am rise, even on weekends, though his sleep time would average in excess of eight hours for the first time.

The remap had convinced the parents that progress was still being made, and the sessions were worth the investment. By session twenty-five, we had been working together for eight months, including various vacation times. The results were now evident: Farouk had found acceptance by his classmates for whom he was, rather than ‘class clown’. Friends (!) came to play with him at his house, and the long school bus trips were no longer incident-prone. Maturity improvements, which the brain map showed, were evident cognitively and emotionally. Farouk was no longer the sole star of every show, but sensed and understood social emotions and felt part of something bigger. He had evolved from his gifted, outsider role and developed a healthy sense of self-worth, fuelled by feeling appreciated.

His sleep improved substantially, reflecting in his demeanour, composition, brain map and his parents’ ability to recuperate, all of which resulted in a noticeably more harmonious home setting. He showed greatly improved emotional maturity and insights, and was entertaining his little brother in a constructive manner. His parents were happy and appreciative, glad to have persisted. Farouk was on a new trajectory that he maintained post training.