Transform Trajectories with Neurofeedback.

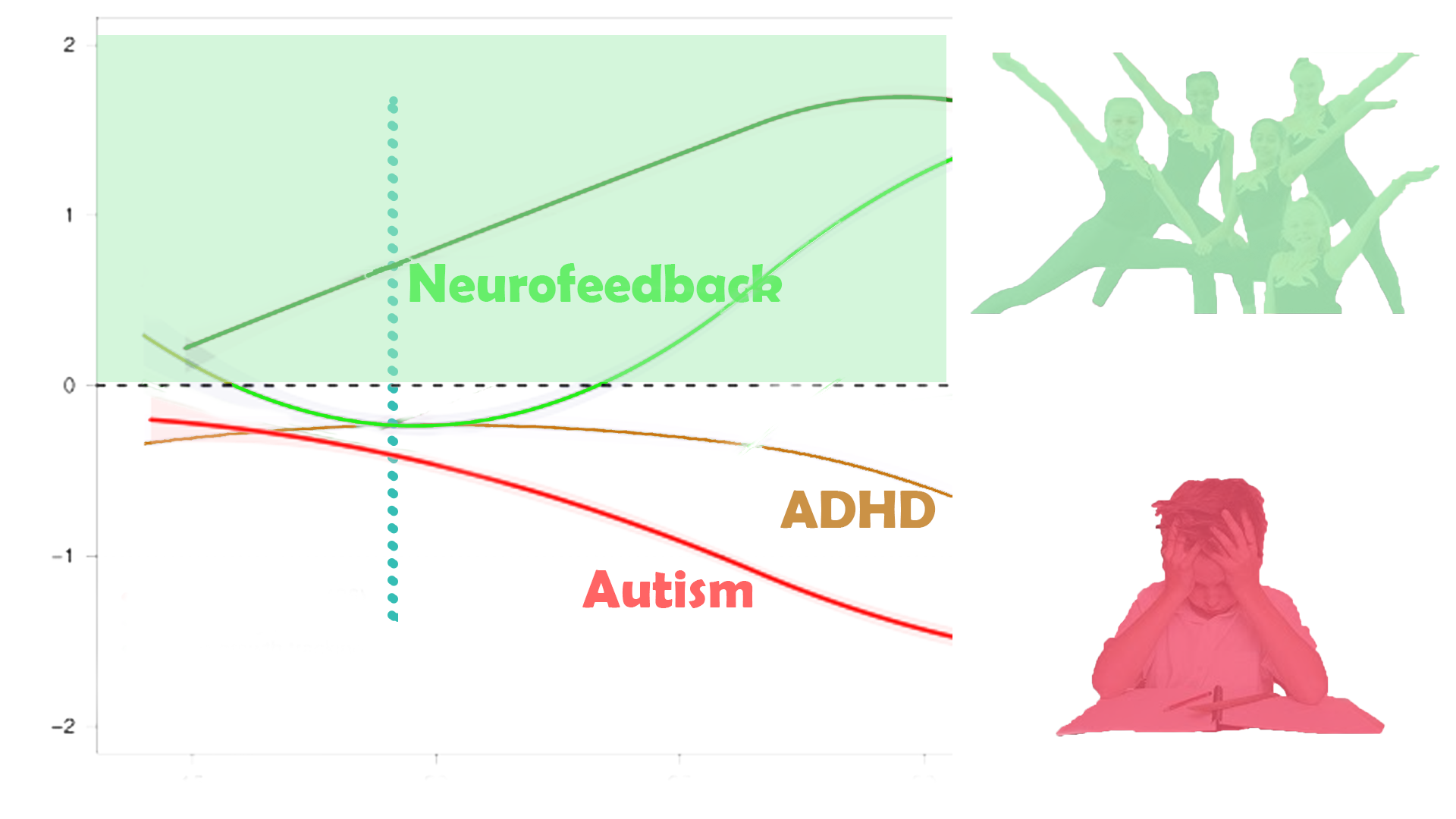

Neurofeedback training is a complementary therapy approach to helping young people attain their best developmental trajectory and thus maximise their opportunities, in a short time period.

Case Studies

Case Studies

Deirdre’s daughter Monica, 10, suffered from severe intractable epilepsy, with up to twenty awakenings due to heavy seizures in a night. While working with Monica, we also did neurofeedback training with Deirdre. Effectively in a state of constant alert and hypervigilance, Deirdre had a strong grounded personality, which showed in her brain map. Nevertheless, the physical and emotional strain was taking its toll, in particular on her sleep, and consequently her ability to focus on her writing project, while managing an impending divorce and relocation. Within the first sessions, her sleep improved substantially and she felt more productive.

"I felt so calm last night! And slept like there were magnets between me and the bed. 10 hours straight."

"Slept like a log."

"Since I started neurofeedback training, my dreams have come back!"

Client testimony.

Lorna had enjoyed what from the outside appeared to have been a privileged life, having enjoyed private education, a lucrative and indeed fulfilling role in the family business, and accumulated some reserves. She had been medicated for bipolar disorder and ADHD from the age of eight, in what she felt was a suppression of her bubbly personality that didn’t conform to parental expectations of ‘order’ or ‘normal’ behaviour. She had always been social and outgoing, enjoyed boarding school, yet she now felt things had come to a head and that she was not living to be the person she could be. Instead, she believed she had conformed to the wishes of her family and ignored her own needs, emotionally, socially, and fundamentally with regard to her identity. Mood swings, disturbed sleep, lack of focus and self-critical thoughts deprived her of joy in her life. As opposed to deprivation of nurture, Lorna had been domineered by her parents, and not been able to develop her own sense of self-nurture. Her identity and sense of self worth were shattered.

Within five sessions, Lorna’s sleep improved noticeably, as did her energy and motivation. She enjoyed doing long sessions, in particular the film “Now, Voyager” with Bette Davis reminded her of her upbringing and situation. After ten sessions, Lorna began working with a talk therapist to reorganise her life and ambitions – teaching in India was a dream she thought could be realised. Her sense of despair had disappeared, and yielded to a slightly overly self-conscious anxiety, which was the first step past numbness. Lorna’s productivity improved and she began to set herself higher goals, leading to some frustration, yet this substantially contrasted with her previous despondency. A further few sessions helped with the self-blame and internal chatter, and Lorna is on a good trajectory.

Maria, 77, an avid reader, discovered in her 60s that she had an irreversible eye condition, a glaucoma, that was causing her tunnel vision. She was able to stabilise the development with medication, yet it led to a few nasty falls, one of which left her concussed. A Kaiser Neuromap showed the expected areas of brain hypometabolism, and we trained her accordingly. Ten sessions later, her sleep was restored, as was her perceived memory, and a remap showed that the brain areas had responded. She felt more productive and grounded and enjoyed the experience of watching multiple movies, her favourite being with Audrey Hepburn.

Marcus’s wife had suspected that certain of his mannerisms had changed, he had become more impulsively aggressive at minor things that changed his routine, and she believed his gait had changed, beyond the mere effects of working from home for the last, stressful, two years. Socially withdrawn, Marcus was focused on his consulting work which had started to pick up again. The joy in his life was lacking, despite having a supportive family.

A brain map revealed some unusual areas of hypometabolism, that would warrant further investigation into whether they are early signs of neurodegeneration, possibly Alzheimer’s Disease. There are certain non-specific neuromarkers, as well as expected reduction in functional connectivity of the corpus callosum that joins the two brain hemispheres. We also found signs of emotional stress and a tendency to internalise, and excessively blame oneself. Two neurofeedback sessions based on these findings returned Marcus’s sleep to a level he had forgotten existed. He became more focused on his work and related social interactions, and had the best financial year of his career.

Linda had been betrayed by her husband. The realisation set in just before her fiftieth birthday. In her second marriage, living in her dream house with an eleven year-old daughter, she felt vulnerable and despaired. They had gotten through the lockdowns as a family, while her social life suffered, and she no longer felt her bubbly self. On top of this she was going through menopause, a disorienting experience, and her daughter was striving for teenage independence in a most hurtful way. Linda had experienced depression before, tried every medical and alternative healing path, and even been to rehabilitation as a way of setting a line to her partying lifestyle in her twenties (“rehab doesn’t work. I’ve made great friends there though!”). She knew there was a resilience in her, which after all had enabled her to transition from being a single mother with an insecure singing career to affording her current lifestyle and the stability it represented. This was now shaken.

Self-doubt and introversion were not her natural habitat, yet she felt isolated, and even began to think she had incurred brain damage as a result of her youthful excesses. Linda was taking anti-depressants and immersed herself in a temporary sales role, which had just come to an end. With time on her hands, she decided to try neurofeedback training.

Visibly nervous excitement before the first session quickly subsided. We started with a brain map, and just wearing the shower cap-like recording device made her feel calm and sleepy. This takes about half an hour, and we quickly proceeded to do a first training session. The cap is replaced with three sensors gently fitted to her head at the areas we look to train. Settling for a Robert de Niro film, Linda was quickly immersed, relaxed and amused. The morning passed swiftly and she was on her feet ready to pick her daughter up for school after the session ended. She noted that her sleep was particularly deep that night.

Linda’s brain map showed substantial deactivation of her prefrontal cortex, something she worried was a result of historic substance abuse. A remap after ten sessions showed visible improvements on this metric, as encouraging as her other improvements in mood, focus and self-confidence.

Intrusive, self-critical thoughts subsided and her motivation returned along with focus and deliberation. She felt particularly productive after each session, and this gave her great confidence. Changes were apparent in every way. Even her husband was amazed – “you’re back to your bubbly self!” Linda began feeling a healthy sense of detachment, and was no longer lifting the weight of the world by herself. She had gone from being reactive and despondent to taking control and setting the rules, which her husband obligingly acquiesced to.

A former singer in a band, she started humming tunes to herself again, and there was music playing in the house, replacing the solemn silence that was deafening upon our first meeting. Soon, projects began, she replaced artwork in the living room and began some redecorations.

Being on her own was no longer her refuge of choice; instead she rekindled productive relationships, and set aside people and places that were soaking up her energy. Her schedule filled, as she accomplished her spinning workouts before our sessions, and project partners were waiting outside as we finished.

Linda started to accept her marital situation, redeemed her sense of self-worth, and found a way to make partnership and parenthood work beyond traditional confines.

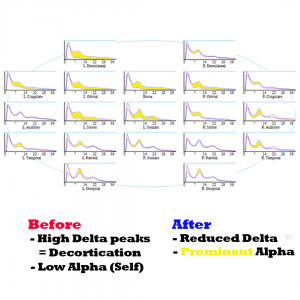

Her brain map corroborates the transition: previously absent alpha peaks emerged visibly, mirroring the cognitive resuscitation she was experiencing. Other vulnerabilities in her initial brain map included:

- mood control;

- lack of emotional safety, or feeling ‘underloved’, both by family and the world at large;

- heightened auditory sensitivity and a tendency to over-attribute emotional content into how things are said;

- focus and planning issues;

- various anxieties – “what’s next”, social anxiety, a sense of everything being directed at her, hypervigilance, and emotional betrayal

- disengagement from her surroundings.

Linda did twenty neurofeedback sessions, over the course of seven weeks, usually three per week. During this time, she had dropped the use of anti-depressant medication (in consultation with her prescribing GP / medical doctor). We did a remap after ten sessions, which showed substantial changes in her overall brain activation and guided the next ten sessions. (She had already commented, “It’s worth it!” after session five). After twenty sessions, Linda’s perceived transformation was corroborated by her final brain map. Of particular note is the way her immediate family embraced the changes, as her daughter began confiding in her.

Anna was prone to strong intra-day mood swings as well as having endured a manic episode, during which she became the subject of financial and emotional exploitation. Importantly, Anna was not psychotic; however she suffered from strong attachment disorder, fear of abandonment, some social awkwardness as a result of an impaired sense of self, and lack of ability to rationalise emotions, despite her warm demeanour.

Following a particular slump triggered by betrayal, and being subject to physical violence, she began neurofeedback sessions. Her sleep improved immediately, as did her outlook. Within five sessions, she had become her usual optimistic self again, and began looking for a new vocation. Within weeks, she had a new job that combined two of her passions and talents, and on a solid path to recovery and forgiveness.

Anna’s mood regulation has substantially improved during her ten overall sessions; she feels more grounded and motivated, while enjoying the cause of her work and the new people she is meeting.

Stephanie, 40, had recently suffered numerous destabilising incidents and conditions that deprived her of her joy of life and made everything seem extremely stressful. One night while preparing dinner, a confluence of her husband’s criticism, her kids screaming and the music on the radio overloaded her senses and she smashed a plate in desparate frustration. It was as if everything was directed at her, and her mood swings and lack of emotional support exacerbated the erosion of purpose she had come to feel. The previous years had deprived her of both parents, and she had ceded freelance work to raising her small children and looking after her ailing mother. Next-door building work continued throughout lockdown, and the family was on the constant verge of deciding to move. Furniture and clothes were packed, and the idea of nesting could not seem more remote. Stephanie felt under constant assault while not progressing personally or professionally. This strain entered her previously strong relationship with her husband, himself under substantial work pressure. Having self-diagnosed as PTSD, both decided to do twenty neurofeedback sessions.

Within a few sessions, Stephanie’s sleep was restored, and she became more motivated and relaxed. It no longer felt as though everything was directed at her, and she was able to respond to unexpected outcomes flexibly and with humour. This did wonders for her relationship, and she felt her children sensed this too. A brain map confirmed this progress.

Mary, 35, had contracted Covid in January and had almost been hospitalised. Six months later, she was still working part-time from home and felt like a shadow of her former self.

She was suffering from fatigue, anxiety and depression, and her sense of smell had not recovered. Brain fog, which could also be attributable to her perimenopausal stage, significantly reduced her productivity and confidence.

Mary’s sleep improved from the first neurofeedback session, as did her physical stamina.

Within three weeks, or five sessions, she noticed her sense of smell had begun to return.

Motivation and focus improved substantially through session ten. Mary felt reinvigorated and her self-critical thoughts subsided. “I’m there for my family again!” she commented.

We did another seven sessions, now spaced weekly, during which Mary remarked that she had never felt a clearer mind before.

It is not suggested that neurofeedback is a “cure” for issues arising from a Covid infection, and we will never know what caused her sense of smell to return. However it was reassuring to see how Mary’s general sense of self and well-being had improved during the time we were training.

Camilla had been diagnosed with anxiety, panic attacks, associated insomnia and mild depression. She was prescribed two anti-depressants – Mirtazapine and and SSRI – which she was able to reduce to a minimum dose over time. During the last three years however, she had six relapses, each following a similar pattern: Stress (emotional and work-related) and fatigue precipitated intrusive thoughts and worries, setting off a familiar path of insomnia; consequently higher anxiety, increased stress levels leading to panic attacks and depressive symptoms. The first few episodes were stabilised by resuming Mirtazapine, which helped restore sleep. The subsequent ones however failed to respond, taking months to stabilise sleep and reduce anxiety, which involved having to take time off work. In addition, she began to have somatisations, beginning in the spine and ultimately reaching her face. Migraines began to reappear when she became excessively tired.

Guided by a brain map, we began doing neurofeedback training twice a week. Camilla’s sleep became sound after the second session – “I feel pleasantly knocked out” – and she decided to reduce her Mirtazapine dose gradually in accordance with her prescribing GP. After eight sessions (four weeks) she was on the lowest dose, and even this left her feeling very groggy in the morning. Camilla had regained confidence in her ability to fall asleep, and stopped using Mirtazapine completely. Her anxiety levels were at their lowest, and she had began to work again, leaving a corporate environment to work with children in a mental health setting – a stressful yet engaging and meaningful activity. Her motivation had reached new levels, and she felt stable and confident, which showed in her stance and demeanour.

Ten sessions of neurofeedback training (each two hours) were sufficient to stabilise Camilla, restore her ability to sleep, and the confidence therein, as well as improving sense of self-worth, focus and motivation. She has not felt the need to use Mirtazapine again since.

Three months later, Camilla reports a major improvement in how she is able to set boundaries, both at work and in her personal life, and not neglecting her own well-being.

Janet, 56, was bursting in her every capacity – as mother of two teenage daughters, wife of a Long Covid-suffering income producer, daughter of an ailing mother with dementia, sister of a libertarian, care-free brother whose involvement with his kids contrasted starkly with her own, friend of contacts she had not had for three years since lockdowns, and undergoing her own menopausal transition.

She had spent the first term of the school year under severe stress, committing herself fully to support her two adolescent daughters, and inserting herself further into every fibre of their lives. She acknowledged that this was the reverse of how her brother was managing his children’s transition into early adulthood. Her own sleep had not been great to start the term with, and the built up worry, anxieties, and pre-existing mood control issues were exacerbated by the stress. Afraid of losing control, and the pending next stage of her own life once her children were going to go to university and leave the house, she compensated with surrendering any own motivations to perceived helpfulness and dedication.

Janet’s career as a casting director had been put on hold when she met her older husband John, whose banking career enabled them an adoption of two infant girls as she was infertile due to an autoimmune condition. In perceived competition with John’s two adult boys from a previous marriage, the girls were enlisted in the same schools. Insecurity and racism plagued their early upbringing, and they were now completing their Six Form (11-12th grade) in an acceptable private school. So big had the strain been on them, along with individual trauma, that both had mental health issues we resolved with neurofeedback training before and during term.

Janet had developed a paranoid cynicism that preceded all social interactions, as if to purposefully conjure up antagonistic reactions in an attempt to prove the worst and thereby achieve some sense of control and certainty. She was ever more convinced of intrinsic racism and antagonism towards any of her causes, and complained about the abolition of social distancing and other Covid measures that had happened over a year ago by now. Her overbearing intensity was difficult to dispute, and it appeared that her children, and husband, were suffering from her lack of self-insight. She would frequently break down when out of sight of her children, upset when her husband, himself suffering from Long Covid symptoms, found the occasional energy to call her ‘neurotic’. It would take a year after her daughters for her to commence neurofeedback training for herself.

Unlike her daughters, and her husband, Janet found it difficult to even tolerate opinions and views other than her own. Any perceived opposition, no matter how well-meant, would trigger her, and she had a tendency to infer the worst. Physiologically aroused, she would immediately turn combative and seek to quell any source of dissent or alternative point of view. This inflexibility applied to the most mundane of issues, such as changes in recreational plans for the day, to political views and current affairs, as well as deep-rooted convictions regarding the Covid pandemic and its resolution, which was being handled completely unsatisfactorily three years after the first lockdown. Janet’s autoimmune condition made her feel particularly vulnerable, and to her, masking and social distancing provided the minimum necessity in public interactions. She saw herself as the only agent of sense and pragmatism in her household, and therefore set the rules. The family was confined to isolation from the first lockdown. Physically, they were staying at home and not going to restaurants theatre shows as in the past. Socially, movements and interactions were severely constrained and limited to family outings. Meetings with friend were rare and heavily vetted, in particular with respect to Covid protocol observation but also perceived sense of responsibility. Volunteering projects, birthday parties and even cinema outings were off-limit. Living between two homes, both far from school and other classmates, furthered this separation. Her daughters were meanwhile the only ones in their class to wear N95 facemasks at all times – a condition that eventually got relaxed regarding outdoor breaks. Janet was driven by her perceived need to be involved and in control.

As a result, Janet was finding it difficult to feel part of something bigger – the outside world had firmly conspired against her, and from a neural perspective, this caused great instability. Her moods were also subject to violent, and fast, swings. Smiles and motivation could cede to despondence and crying in despair within a few hours. It was as if her fighting spirit was the only thing that could fire up her will power, at great emotional and energetic expense. Combat was her main driver, and she would find antagonism in anything and everyone, any fault triggering a polarised perception. School provided an outlet, as she got involved in every any aspect of her children’s education, trying to impose mask mandates there and actively communicating with teachers about coursework and teaching methods. Only parents with common grievances were part of her circle, and still this fluctuated by topic.

Unable to fall asleep easily, she would research the internet late into the night, and she was woken up easily at any time. Janet’s mind was racing at all times, and she felt like she was having to defeat internal voices of dissent when left to her own devices. She had long felt a dissociation from her body, and couldn’t remember the last time she had been given a hug. Her daughters’ growing desire for independence, and the prospect of complete solitude once they would graduate in a year’s time, frightened her. She was distrustful of medical doctors, especially as most had ceased to wear face masks, and had only one (paid) confidant in form of a psychotherapist who was willing to agree with her on everything.

Janet’s obsession with “wanting to be there completely” for her daughters’ final two years of school was placing a burden on her environment. She was at war with the headmaster, in particular regarding the laxer Covid protocols; teachers, concerning their methods and interactions; society at large for the cessation of vigilant pandemic measures she considered premature; her husband, whose despondence she could not attribute to her domination on all issues; and even her daughters’ search for privacy and independence, which she took personally in a highly emotional manner. Seemingly well-intentioned, her actions were socially disruptive. On a long-awaited family summer vacation, she prevented her daughters from mixing with peers out of fear that they would be drawn into illegal activities that the law would interpret differently with respect to them due to their ethnicity. Dinners were cut short when she felt others’ views were out of order, a frequent occurrence. Her daughters were showing signs of strain throughout the summer, one threatening self-harm and the other suffering from panic attacks. Both overcame their challenges with neurofeedback training.

Janet’s body began to give. A year after her daughters’ neurofeedback training, driven by the same ideals and obsessions, Janet began to experience cardiovascular issues. Heart dysrhythmia was diagnosed and treated with medication. She found it difficult to accept the advice of rest and detachment. Thoughts became intrusive, and even her therapist found the courage to voice their concerns about her trajectory to her. It was just before Christmas that she decided to reach out for neurofeedback training, whose success she’d witnessed in both her daughters.

We began with a brain map, which confirmed her relational thinking, mood and sleep disorders, various trauma markers, and sources of anxiety. Knowing, and fearing, that “this could change me”, we talked through the findings, which have an objective nature due to being based on physiology, or observed functional connectivity between brain areas, rather than being a subjective award of pathologies by an authority, for most of whom she harboured deep contempt. The fear, “could this change me”, had already been objectively overcome with her commitment to an initial brain map and session; subjectively, the prospect of achieving better sleep and reduced internal chatter had become sufficiently appealing.

As a former casting director, Janet retained her interest in art and theatre, and chose her favourite films to watch in session. Quickly engaged with the content, sessions felt non-invasive enough for her to tolerate. Neurofeedback sessions obviated the need for overt introflection, by contrast to talk therapy, and avoided triggering her with the result of reanimating her combative style. Her views were not questioned, and her brain trained to achieve a healthy sense of detachment in the first instance. This took a few sessions, during the course of which she noticed her sleep improving drastically. Being able to let go of her thoughts at night and settle into a deep state of relaxation was previously a feared scenario, yet this began to feel more natural and energising with every session. After five sessions, she noticed how her behaviour and reactions had began to change. No longer anticipating the worst in every situation, she felt a calm optimism and motivation that she could not recall having experienced for a long time. Relations with her supportive husband improved to everyone’s relief, and her daughters’ were positively surprised by her evolving lack of invasiveness. For the first time, it appeared that Janet was able to recall her own frustrations in her childhood at being micromanaged by her parents, and share this admission with her family. To everyone, it felt as if a weight was being lifted.

Encouraged by the positive feedback from her immediate environment, Janet continued with weekly neurofeedback sessions. At one point, she felt particularly emotional after a session, and found herself confiding in her brother on a long phone conversation that night. She felt lighter as a result, but was plagued with some remorse and guilt about how she had been acting. A supportive environment helped her achieve self-forgiveness and a more positive outlook. Reminded of her progress, she drew strength from the shape of her changed trajectory. It was as if people started to come closer to her, piercing an invisible wall she had built up around herself. Janet began to feel part of a social fabric that had an enabling quality and created a source of stability. Her moods and motivations became more stable, and she resumed interests in art that she had parked long ago. Within two months, Janet was talking to people from previous work-related circles who encouraged her to resume projects she had previously excelled in. Meetings followed, and melded into a social life. Physically, Janet felt better rested and ensconced in her body; hugs mattered, and her sensitivity was reciprocated. Embedded in a supportive environment, Janet began to flourish. Intrusive thoughts became ideas, and fears turned into surmountable challenges. She wished that she had begun training earlier, in parallel with her daughters, and was now living in the moment.