Neurofeedback for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Autism is characterised by an inflexibility that manifests in impaired social interactions and communications, and repetitive behaviours.

It starts from an early age, and adversely affects social integration, leading to lower expectations regarding developmental trajectories.

With Daniel Webster’s Neurofeedback, we can help the brain become more flexible, mature and integrated. This enables better social integration and resets trajectories, thus improving quality of life and promoting the full realisation of talents and potential.

The process is non-invasive, evidence-based, and enjoyable.

Daniel practices in London and Edinburgh, and is available for home visits internationally.

Client Feedback

Overview of Daniel Webster's Neurofeedback for Autism

Changing Trajectories

Developmental expectations and trajectories are dampened by reduced social integration and cognitive inflexibility, and higher care or support requirements.

Early intervention can reduce this gap with peers and produce virtuous feedback loops.

Daniel Webster’s Neurofeedback produces transformational results in all age groups, as young as two.

Personalised Training

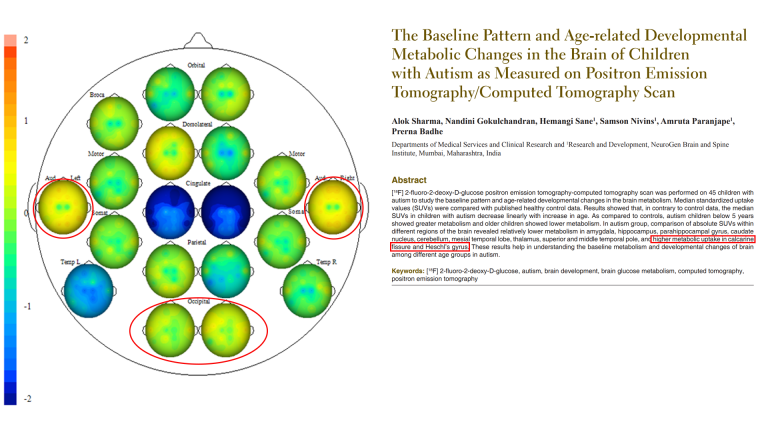

qEEG brain maps are a non-invasive way of analysing functional connectivity of over 40 brain areas, a measure of the health of the brain’s ‘wiring’, or relative contribution of each component.

There are common neuromarkers in persons with an ASD diagnosis (though a brain map is not a diagnostic tool). Autism is a heterogeneous condition, requiring a personalised approach, bespoke to the person’s challenges.

Daniel Webster’s Neurofeedback is personalised brain training that is enjoyable – the person watches a movie of choice, the feedback is subtle (not stop-start) and training is passive, requiring only attention to the movie.

See here for more information on How it Works.

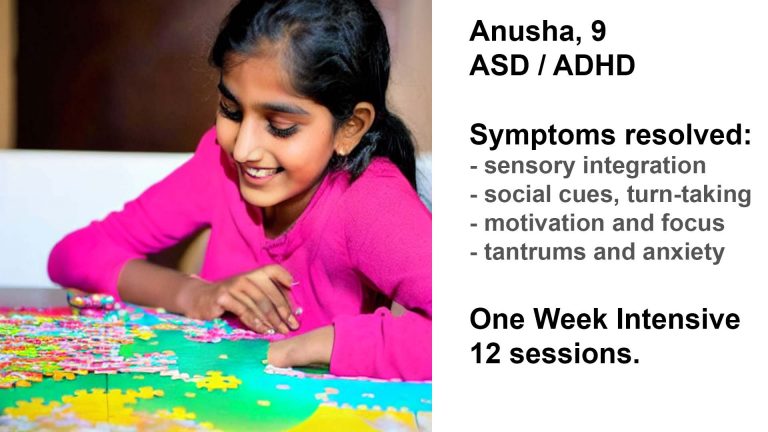

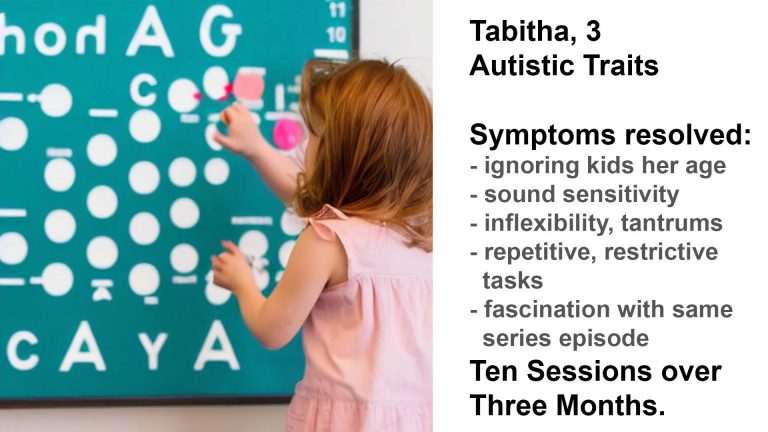

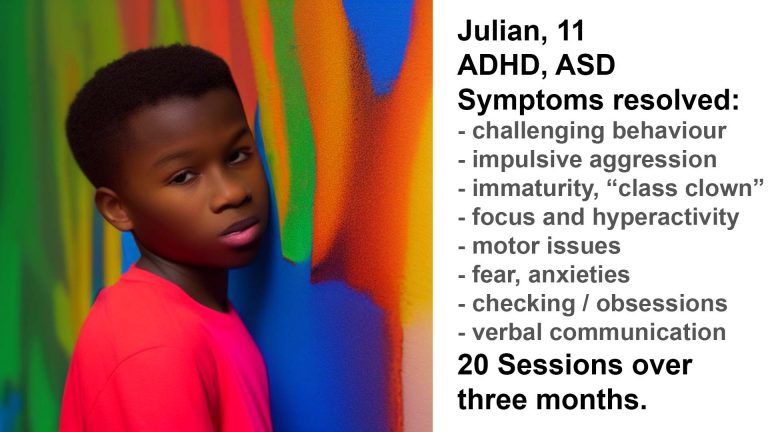

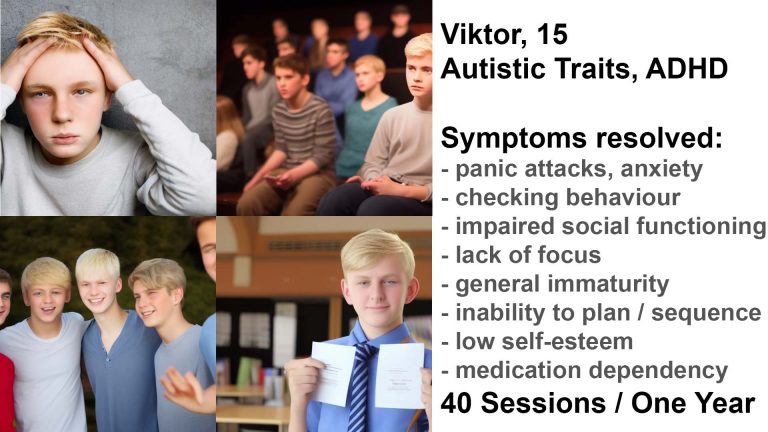

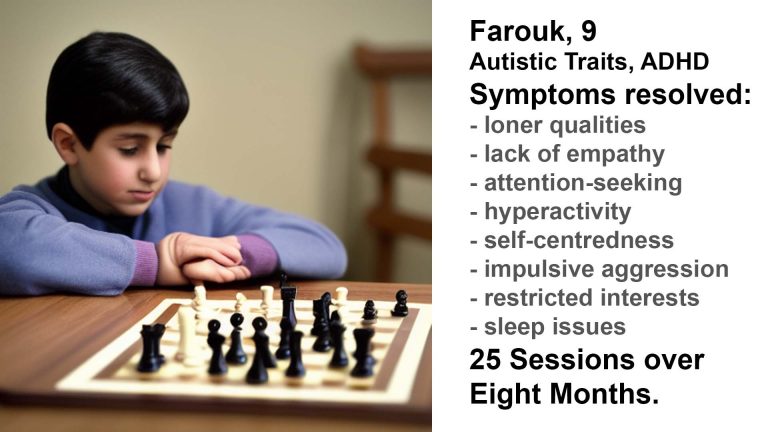

Case Studies

Daniel’s Neurofeedback is personalised and suited to all age groups.

Early interventions can resolve developmental gaps with peers and accelerate maturation.

Fast, transformative results from age 2 to adults are summarised in the case studies below, click here.

Research

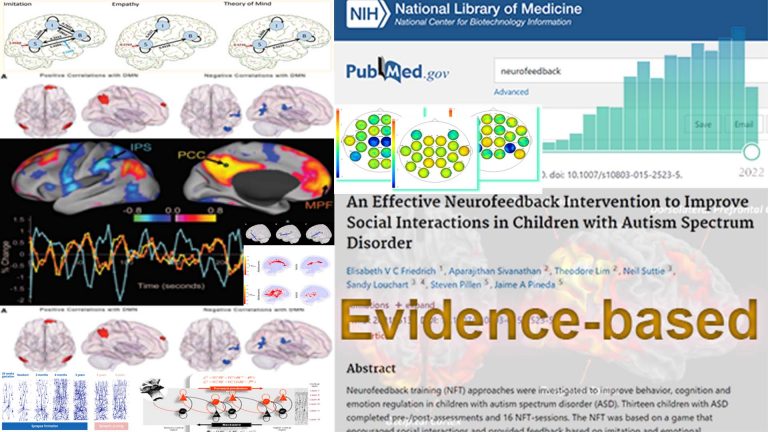

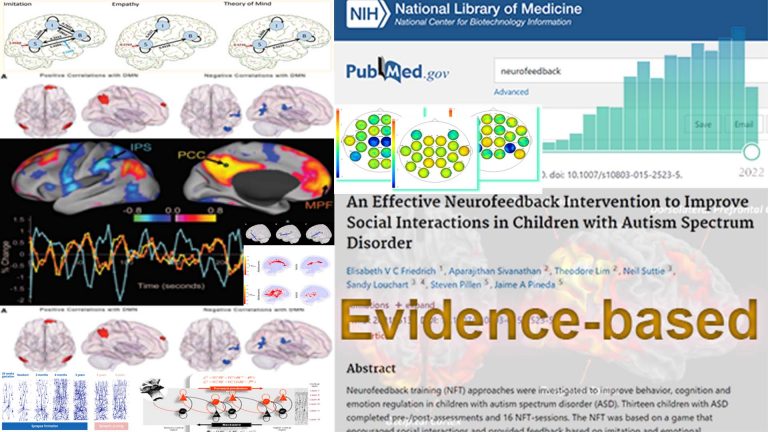

Neurofeedback is evidence-based, with over 2,800 supporting studies.

Research shows that Neurofeedback for Autism generates lasting improvement in executive function, reduces stimming, improves speech and communication, reduces aggression, and has calming effects that enhance cognitive flexibility.

The pro-social effects are produced by beneficial changes in functional connectivity.

Daniel Webster

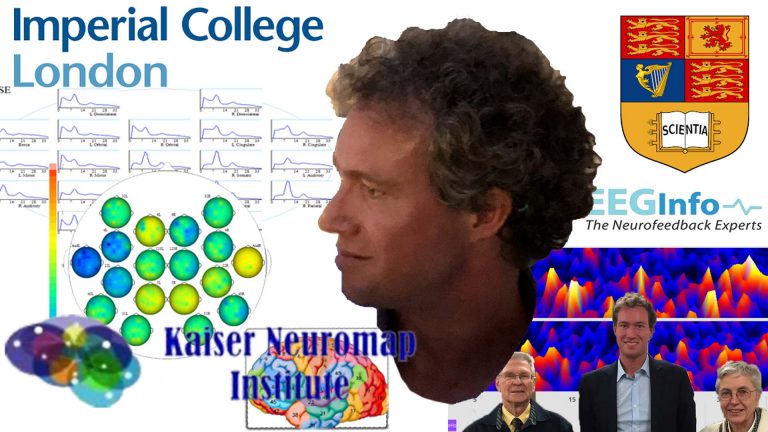

Daniel Webster uses the most advanced neurofeedback methods.

He was taught in LA by the founders of the field, Dr. David Kaiser and Sue & Siegfried Othmer.

Daniel continues to research and advance neurofeedback protocols, and has recently presented at Africa’s first conference for autism and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Case Studies

Daniel Webster uses the most sophisticated and insightful qEEG interpretation methodology to reveal individual issues and form a neurofeedback training plan.

Aspects of Autism

Self-Regulation

Fear and anxieties have neural correlates that are typically dysregulated in autistic children and adults. Some of these overlap with sensory integration issues, and training the relevant brain areas provides significant calming.

– reduce fear, auditory sensitivity and anxieties

– strengthen key brain network functionality to improve predictive capacities and abstraction abilities / learning

– reduce inclination towards impulsive aggression, and further rage, when outcomes don’t match expectations

– restore/create ability to self-soothe and self-nurture

– improve planning, focus and motivation

– train self-other distinction capacity, appreciation of social boundaries, perception of other and social emotions.

Improved flexibility leads to an accelerated maturation and new capacities for self-realisation.

Sensory Integration

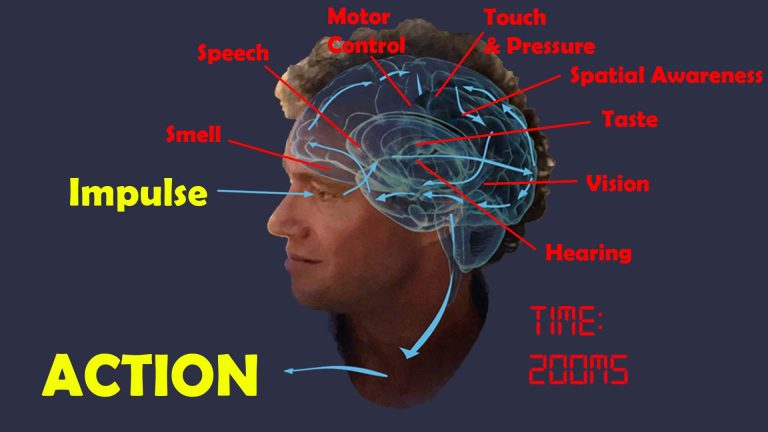

There are distinct brain areas that interpret the respective sensory input, and through various convergent processing stages – multi-modal association areas – the brain constructs a scene, and understands where we are with respect to our environment. For example, the back, or occipital area of our brain is where visual information is analysed; auditory processing occurs in the temporal lobe, close to our ears.

When any of these brain areas becomes dysrhythmic, our interpretation becomes distorted, for example, we can become hyper- or hyposensitive, as is seen in various symptoms of autism.

Individual sensitivities vary substantially. With a brain map, we can determine which particular sensory processing areas are vulnerable, providing a personalised approach.

With neurofeedback, we can train the brain areas relevant for efficient sensory processing and integration. Hypersensitivity to sound, as well as overly emotional interpretation of what is said, becomes attenuated and flexible. Body awareness and motor control improves, as does facial recognition. This is evidence-based, and confirmed by outcomes from our training.

Social Interaction

Making friends and forming alliances is a mammalian quality that is most pronounced in humans, allowing us to achieve exceptional, civilisation-building accomplishments that we could not produce on our own. Social functioning is a key component of this, and we can help persons on the autistic spectrum improve this quality substantially for their own empowerment.

With Daniel Webster’s Neurofeedback, we can train:

– Recognising the needs of other(s), and accomodating these in a way that preserves our own needs and ambitions, is key to fluid social interaction, such as turn-taking.

– Easing anxieties and reducing phobias. There are numerous cortical sources of anxiety. It can take the form of social anxiety, where a person doesn’t understand social complexities or emotions; a “what’s next” anxiety where we are unsure of our relationship to the scene in front of us; relational thinking, where we are wired to think that all sensory stimulus is directed at us, and fail to feel sufficiently detached; or excess concern with our appearance.

– Predictive capacities are frequently impaired in autism. This can include being unable to catch a ball or anticipate motion of objects in general, an often dangerous deficiency in the outside world. It further extends to modelling others’ behaviours and needs, impairing our ability to show consideration and integrate into more complex social situations. Inflexibility with regard to routines and learned behaviour is another frequent manifestation, as these feel safe. On a more nuanced level, impaired predictive capacity can lead to misunderstanding incongruences, taking things too literally, and thus failing to appreciate humour, irony or satire.

– Social rules are an important part of societal interaction. These can be non-explicit, and may comprise exemptions, requiring a non-polarised appreciation that is situation-specific. We can train this flexibility, both with regard to perception and manipulation.

Communication

One in four persons with ASD are non-verbal, and 40% of all children referred to an autism clinic have significant speech delay, regardless of diagnosis. There is a strong link between language and social skills in autism.

Speech development has numerous components, all of which have neural correlates, meaning there are brain areas contributing towards language comprehension and generation, which have to mature and work together efficiently. This means we have a chance to improve speech generation by training the brain, and both research and experience confirm this. The research below illustrates how we can assist with improving necessary building blocks that contribute to a person’s development of speech and language capabilities. Neurofeedback has been shown to improve speech and language competency in autism.

Speech and language development are also a function of social reciprocity, both with regard to initiation and reception. It should therefore not be seen in isolation, and rather as an accompanying component of improving effective synchrony with the social environment.

Personalised Brain Training takes a holistic approach to improving social integration by way of training various features of cognition and consciousness, including sense of self, joint attention, Theory of Mind, focus, mood regulation, behavioural challenges and communication, both verbal and non-verbal.

Comorbidities

Autistic Spectrum Disorder presents with many comorbid disorders, often not diagnosed explicitly.

Mood, personality and attentional disorders have neural correlates, and with a brain map we can disaggregate the formal pathologies by attributing behaviour patterns to dysrhythmic brain areas.

This allows for a personalised, holistic approach to improving flexibility, maturation, social integration and personal development.

Neurofeedback is shown to be safe and effective for many pathologies.

Changing Trajectories

Neurofeedback training is is applicable from an early age. While some diagnosis parameters maintain that autism can only be assessed from age 3, signs can emerge much earlier. In our experience, early intervention can help averse developments substantially and transformatively (see case studies).

An estimated 15-40% of ASD cases are deemed regressive, where normal development up to 15-19 months is followed by loss of vocabulary, reduced social interaction and responsiveness, and sometimes repetitive play behaviour. We do not provide diagnosis.

Future care efforts and costs can often be substantially reduced as a result. The average lifetime cost of supporting an autistic person is estimated at $3.2 million. In comparison, neurofeedback training, while cost-intensive, is a fraction of this.

Enabling greater talent expression can lead to improved earnings potential and financial self-sufficiency. These ‘dividends’ materialise over time, and their present value can exceed the investment made in Personalised Brain Training at an earlier stage by multiples.

For example, a high-functioning adult with ASD can enjoy structured day-care within, or complementary to, a supported living facility. Another possibility is that supported living is either not suitable, and they live with their primary caregivers (e.g. parents), adding to their financial burden. Changing their trajectory by improving their social skills and related mental health issues could launch them into a structured workplace, boosting their self-esteem and confidence, while providing them with an income.

Such interventions can improve quality of life significantly. Increasing independence, self-fulfilment and expression, and sustaining friends and social interactions are immeasurable additions to a vulnerable person’s life.

Neurofeedback training is non-invasive and medication-free, and this organic treatment approach respects the individual’s choices.

Personalised Approach

The idea of looking into the brain to identify issues seems intuitive. It was only in this millenium that such an approach became feasible in a meaningful manner. Brain map interpretation methodologies vary greatly. Daniel uses a method that lets us assess maturity of Brodmann areas to get a granular insight into functional connectivity – how individual brain areas communicate with each other. This lets us see where the challenges are with respect to sensory integration, network integration, social brain maturity, and many other behavioural aspects.

Research into the functions of Brodmann areas is now abounding at over 200 PubMed reports per year. Immersed into this exciting field, we find neuromarkers for behaviour patterns from scientific fMRI studies that support findings of our brain map technology.

Importantly, this approach lets us relate behaviour to physiology, rather than, say, dated psychological models. Training the parts of the brain that we find are dysrhymthic, we can accelerate maturity with the advanced neurofeedback methods Daniel uses. The results are experienced cognitively, and re-maps confirm this progress.

Research

Neurofeedback training has been shown to be a safe, feasible, and effective therapy approach to Autism Spectrum Disorder across all ages.

Multiple studies confirm:

– improved cognitive function in social, thought and attention domains

– improved cognitive flexibility

– reduced stimming, improved speech and language competency, use of imaginary play

– lasting improvement in executive function, working memory and processing speed

– improved facial recognition

– better behaviour, including being less aggressive, more cooperative and better at communication

– improved functional connectivity in the social brain regions

– a 40% reduction in ASD symptoms among 89% of participants, and associated changes in cerebral functional connectivity

– lasting improvement in ACC / DMN flexibility, crucially linked to Theory of Mind

– significant improvements in general and non-verbal communication and social interaction

– lasting, and increasing improvements past the training period, in attention control, cognitive flexibility, planning, communication and social interaction

A 9 point improvement in IQ was reported in a large-scale study, alongside decreased ASD symptoms including attention, anxiety, aprosodias, social functioning, as well as academic and intellectual functioning.

Sensorimotor behaviour (posturography) improved in children.

Neurofeedback training has proven calming effects.

Research evidence for comorbidities, e.g. ADHD, dyslexia, depression, anxiety, seizures, sleep and behaviour is shown under the relevant tabs below.

About Autism

Autism can in theory be reliably diagnosed by age 2, though most are not diagnosed until they are 4, and pandemic-related delays have pushed this up to 8 years old in recent years. Boys are four times more likely to be diagnosed with autism than girls, and there are considerable differences when viewed by ethnicity.

There are various views on when and how it develops. Some children exhibit signs from birth; studies suggest that 10-30% of cases are regressive, that is, a child meeting expected developmental milestones begins to disconnect and reverse its development to become diagnosed with autism, around the age of 2 (20 months). Cases of sudden (same day) regression exist, while others are deemed more gradual. Regression usually carries a worse prognosis.

Consensus science knows what is definitely not a cause of autism.

A troubling trend is the significant increase in overall rates: One in 36 children in the US are now diagnosed with autism, that is, in 2020, up from one in 44 in 2018, compared to one in 150 during the year 2000. In the UK, the overall prevalence of the condition is estimated at 1/100, or around 700,000 afflicted persons overall. Per the University of Newcastle, it is 2.8% among boys (1/36) and 0.65% in girls (1/150). The Lancet medical journal records an incidence of 1/250 among 5-9 year olds, 1/4,000 in 20-49 year olds, and 1/18,000 in people over the age of 50.

Since 2020, the number of PIP claims cleared in the UK for Autism Spectrum Disorder has increased from under 600 per month to over 1,900 per month.

Searching for causes has resulted in considerable debate and controversy. What is sure however is that early intervention can dramatically shape outcomes, with regard to development, life quality and care and support needs.

Brain maps and neurofeedback do not provide diagnosis. We can however identify vulnerability to symptoms, and their cortical source, and work on these with training. We can do this at any point in a person’s life, and are not restrained by contradictions between sudden onset of symptoms and diagnostic criteria (e.g. PANS/PANDAS). Neurofeedback is non-invasive, safe and medication-free. Its efficacy with ASD symptoms is evidence-based per the research above.

Case Studies

Daniel Webster uses the most sophisticated and insightful qEEG interpretation methodology to reveal individual issues and form a neurofeedback training plan.

Sensory Processing and Integration

Specific Brain Areas process our Sensory Input

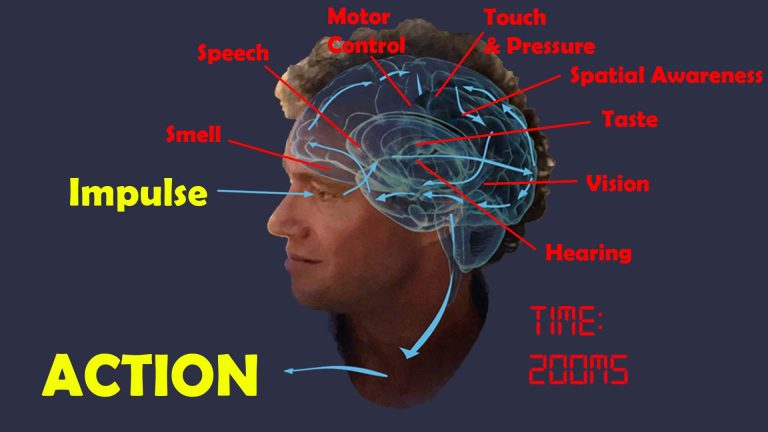

Our brain is the gatekeeper to our senses. It governs our sensitivity, and structures our reactions. Sensory processing and integration issues in autism (and any other pathology) is substantially controlled by our brain. As such it makes sense to train our brain’s ability to discern, process, integrate and monitor information flow generated by sensory stimuli.

Motion, coordination and actions are likewise governed by our brain. In fact, higher level functions of the motor skill processing areas of our brain also regulate our appreciation of social boundaries and personal space.

There are distinct brain areas that interpret the respective sensory input, and through various convergent processing stages – multi-modal association areas – the brain constructs a scene, and understands where we are with respect to our environment. For example, the back, or occipital area of our brain is where visual information is analysed; auditory processing occurs in the temporal lobe, close to our ears.

When any of these brain areas becomes dysrhythmic, our interpretation becomes distorted, for example, we can become hyper- or hyposensitive, as is seen in various symptoms of autism.

Individual sensitivities vary substantially. With a brain map, we can determine which particular sensory processing areas are vulnerable, providing a personalised approach.

With neurofeedback, we can train the brain areas relevant for efficient sensory processing and integration. Hypersensitivity to sound, as well as overly emotional interpretation of what is said, becomes attenuated and flexible. Body awareness and motor control improves, as does facial recognition. This is evidence-based, and confirmed by outcomes from our training.

Our Brain Predicts Behaviour

Sensory processing takes time. From perceived impulse, for example visual input, to a decision and motor action, this can be up to 200ms, or a fifth of a second. To compensate for the delay between perception and reality, our brain needs to engage in predictive behaviour. We are in essence modelling our environment, and confirming predictions with our senses.

On a basic level, this lets us anticipate where a moving object, such as an approaching tennis ball, will be, and plan actions accordingly. Were we to rely purely on responding to stimuli as they are registered through our senses, we would miss the ball, or any other approaching object for that matter.

On a higher level, we apply this predictive modelling capacity to behaviour patterns, including people around us, and events and consequences of actions in general. We are able to plan for the future.

In autism, this ability to model and predict is impaired, or underdeveloped. The extent of this inability varies by individual. As a result, the world is a constant novelty, which can be both fascinating and disconcerting. A preference for predictable behaviour, routines and repetitive, restrictive actions emerges. While this can lead to strengths and specialisations, it is also a disadvantage when engaging with others, or being in a changing environment. Furthermore, a reduced capacity to abstract and learn from experiences is a frequent deficit in autistic persons.

Improving modelling and predictive capacity with Daniel Webster’s Neurofeedback is based on two approaches:

1. developing flexibility in and maturing individual sensory processing areas, guided by a brain map to accomodate individual differences

2. strengthening network connectivity, that is, interaction between brain areas that combine the processed sensory input, and define our sense of self and attentiveness to our environment, including the various networks (Default Mode Network, Salience Network, Task Positive Network / Central Executive Network, Mirror Neuron System).

We do this by training individual sites, as well as various connecitivities, by the simple process of engaging the conscious mind with a reward – the movie – while giving preconscious areas feedback on various training protocols by reducing the volume slightly – yet still audible – and temporarily – fractions of a second – when certain frequency patterns aren’t met. With repetition, this shows the brain a more efficient behaviour pattern, which it will seek to adopt. As such, training is passive, and organic.

Personalised Brain Training uses the most advanced qEEG brain map interpretation method to form an individualised training plan. Our neurofeedback method applies the most effective training protocols with an enjoyable feedback process, watching movies of choice.

Respecting Individuality in Autism

It is important to be compassionate and non-judgmental, so we need to remove standards by which we assess neurotypical behaviour and empathise with the ASD individual: Altered sensory interpretation can cause extreme reactions; reduced ability to plan, organise and pursue a task may result in erratic performance; social skills might need more practice, as do insights into boundaries, rules and personal space; stimulus seeking behaviour might seem out of ordinary yet plausible in the context of the person’s individual reward system.

They might be shocked by views they have not come across themselves and are unable to accept/ tolerate / process; aspects of the other’s appearance might deter them while not being ill-intentioned; turn-taking can be a disorienting concept and break their preference for own rules and procedures; unexpected views / actions might deter them and infer hostility where this is not intentioned.

Changes can be an unwelcome sensory / processing overload which they are not prepared to deal with, causing anxiety and a sense of hostility; adjusting to new situations might overload their capacity to sequence, model new outcomes and retain motivation; this can create a sense of adversity and lack of acceptance, taken overly personally and affecting self-esteem and confidence, especially when a routine has taken time to master and is associated with certain reward outcomes.

Certain behaviours might be responses to a form of sensory overload, and not obvious to spot / make sense of until better empathising or getting to know the individual and assessing the context in which they resort to the behaviour in question. They might be self-protecting, or conditioned into achieving something this way when there are other alternatives that can be taught.

The ability to abstract and learn from behavioural outcomes is frequently depaired in autism. While not an explicit criterium for an autism diagnosis, we see this feature commonly, and it can also apply to persons without a formal diagnosis. With adults in particular, where other autistic traits can be more effectively masked, this can lead to hurtful behaviour. We might assume that discussion of a breach of trust will lead to different outcomes when in a similar situation, however the person is not able to apply a ‘lesson learned’ and repeat their actions.

Personalised Brain Training takes the approach of assessing each individual’s particular sensory, social and cognitive vulnerabilities with a brain map, and training these with the most advanced, personalised neurofeedback protocols.

Social Functioning

Making friends and forming alliances is a mammalian quality that is most pronounced in humans, allowing us to achieve exceptional, civilisation-building accomplishments that we could not produce on our own. Social functioning is a key component of this, and we can help persons on the autistic spectrum improve this quality substantially.

Recognising and appreciating another person’s capacity for independent thought and scope of action is a fundamental component of social interaction, called Theory of Mind. Possibly better defined than its encompassing ASD umbrella, this is an important concept underlying interpersonal relationships. Appreciating that the ‘other’ is not merely an extension of oneself is also a key component of effective parenting.

We have prefrontal brain areas that govern our sense for social rules and self/other distinction. Human interaction is also defined by boundaries: One person’s social boundary is another’s personal space, and vice versa; we thrive when we find the appropriate level of invasiveness versus recruitability. Not letting people into one’s personal space, i.e. excessive obstinacy, creates boundaries, while excessive invasiveness is alienating and deemed disrespectful. There are cultural components to this, creating variability, and as always, flexibility is key. Both features – social boundaries and personal space – are governed by distinct brain areas, which we can train.

Our Mirron Neuron System enables us to learn actions and behaviour from observation, and quickly. This is a well-studied set of neural nodes, or distinct brain areas, that is core to the social-cognitive processes of imitation, empathy and Theory of Mind. We can train these areas, and their cohesion, with neurofeedback, in a non-invasive, medication-free manner.

Social emotions are recognised and processed by distinct brain areas. When these are dysrhythmic, a spectrum of symptoms can ensue. Perception is at the forefront, and our mirror neuron system is a key part of this. Assuming some functionality here, we can then see possible egocentricity bias, meaning that we are prone to making empathic judgments based on our own state of mind while disregarding the other. It can also adversely impact our ability to shift attention and recognise agency. The result is friction with our environment, and a contributor to social anxiety. Training these brain areas leads to substantial calming and acceptance, in our experience.

Recognising the needs of other(s), and accomodating these in a way that preserves our own needs and ambitions, is key to fluid social interaction, such as turn-taking. We rely on a stable and evolved sense of self, something that our Default Mode Network, and its healthy interaction with our Task Positive Network, provides. A core part of Daniel’s neurofeedback is training this specifically, as part of a holistic approach.

Easing anxieties and reducing phobias is an evidence-based effect of Personalised Brain Training. There are numerous cortical sources of anxiety. It can take the form of social anxiety, where a person doesn’t understand social complexities or emotions; a “what’s next” anxiety where we are unsure of our relationship to the scene in front of us; relational thinking, where we are wired to think that all sensory stimulus is directed at us, and fail to feel sufficiently detached; or excess concern with our appearance. Phobias can be an inflexibility when confronted with situations reminiscent of a previous, unpleasant situation. They can also result from sensory overload or lack of processing / integration, such as towards sound, heights, light, taste or touch. Again, we find these resolve with Daniel’s neurofeedback training.

Predictive capacities are frequently impaired in autism. This can include being unable to catch a ball or anticipate motion of objects in general, an often dangerous deficiency in the outside world. It further extends to modelling others’ behaviours and needs, impairing our ability to show consideration and integrate into more complex social situations. Inflexibility with regard to routines and learned behaviour is another frequent manifestation. On a more nuanced level, impaired predictive capacity can lead to misunderstanding incongruences, taking things too literally, and thus failing to appreciate humour, irony or satire. This in turn can lead to misunderstandings that cause friction with our environment. Our Default Mode Network plays an important role here, and it is something we can train to greatly enhance quality of life in many facets.

Social rules are an important part of societal interaction. These can be non-explicit, and may comprise exemptions, requiring a non-polarised appreciation that is situation-specific. We can train this flexibility, both with regard to perception and manipulation.

Verbal and non-verbal communication is a complex subject which is dealt with in this section; we often find substantial leaps in tandem motivation and self-esteem improvements that arise from developments of the above aspects.

Self-Regulation

Common features among persons on the autistic spectrum are fear of unexpected actions and consequences; inability to model our environment and abstract novel impressions; and excessive obstinacy that turns into impulsive aggression and often rage.

Fear and anxieties have neural correlates that are typically dysregulated in autistic children and adults. Some overlap with sensory integration issues, and training the relevant brain areas provides significant calming.

Our sense of self is governed by our Default Mode Network, a set of brain areas that provides the neural basis of self and activates during self-referential thought, day-dreaming and imagination. This network’s activity is attenuated when we are engaged by our environment, ceding to Task Positive Network sites. Our ability to flexibly activate and deactivate each of these networks, in a mutually distinct manner, is key to optimal performance. When this process is dysregulated, issues arise with respect to social functioning as well as compulsive behaviour. Sensory integration issues compound this tendency and we see repetitive, restrictive behaviour patterns that seemingly provide soothing and respite at the expense of detachment from our social surroundings.

Other core DMN sites govern our ability to self-soothe and self-nurture, that is, both to provide a rational way to talk ourselves down from situations, as well as to create an emotionally safe environment. This affects mood control, impulsivity, sleep quality, empathy and self/other differentiation.

In a world that is constantly novel, routine and predictability offer respite. With neurofeedback, we are helping in numerous ways:

– reduce fear, auditory sensitivity and anxieties

– strengthen key brain network functionality to improve predictive capacities and abstraction abilities

– reduce inclination towards impulsive aggression, and further rage, when outcomes don’t match expectations

– restore/create ability to self-sooth and self-nurture

– improve planning, focus and motivation

– train self-other distinction capacity, appreciation of social boundaries, perception of other and social emotions.

Improved flexibility leads to an accelerated maturation and self-realisation.

We have successfuly trained the relevant brain areas to restore a sense of grounding. Behavioural changes are usually noticeable within ten sessions. Concomitantly, we see and sense a relief and new flexibility that is liberating for both the person and their carers / guardians. See Case Studies for examples.

What is Autism?

Autism is a spectrum disorder characterised by social integration issues and developmental delays that can be both physical and emotional. In particular, we can identify and train vulnerabilities to behaviour patterns:

– sensory integration: sensitivity to sound, light, taste and touch, motor coordination; balance, bodily and spatial awareness; speech comprehension and production

– social functioning: social cues, taking turns, Theory of Mind, collaboration with others, social rules and boundaries, self-other distinction

– self-regulation: mood and impulse control, impulsive aggression and rage, fear and anxieties, ability to self-soothe / self-nurture, repetitive restrictive behaviour

– cognitive flexibility: modelling the intentions of others; predicting movements, behaviours and outcomes; updating models and predictions based on observations; adjusting behaviour flexibly and pro-socially.

The result of neurofeeback training is a calmer, better integrated child or adult as we enable them to maximise their true social and productive potential.

Social Development in Autism

Social development may be affected in ASD persons as follows:

– underdeveloped Theory of Mind, that is, attribution of intentions / emotions / perspectives of others, inferring mental states, modelling others’ behaviours / anticipating this

– lack of self/other differentiation

– social anxieties, not understanding social complexity, thus avoiding social contact and practice of social skills

– not understanding social boundaries and rules, resulting in seemingly inappropriate behaviour

– apparent insensitivity to social emotions and thereby missing essential (non-verbal) context

– inability to mirror and establish rapport

– being tired, unfocused or otherwise not showing necessary motivation to sustain social interactions, precipitating a negative feedback loop

The aforementioned developmental issues can lead to a lack of practice and recognition of situations, requiring incrementally more effort and valuable energy resources. Underdeveloped understanding of social boundaries and rules, anxieties, lack of motivation and focus, and feeling of rehearsed isolation further exacerbate this lack of confidence and can further deprive the person of opportunities to learn and gain positive reinforcement.

Speech and language are crucial components of personal interactions, sharing emotions and perspectives, and exercising large portions of our neural networks. A negative feedback loop ensues, as personal development (and confidence) results from our interaction with others, in turn conditional on the physical ability to relate, which speech and language (verbal and non-verbal) are key components. [Still, mere physical presence can be perceived and convey a lot]

Autism Diagnosis Criteria per DSM-5

Autism is diagnosed as follows by the DSM-5:

A: Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts

B: Restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities

C: Symptoms must be present in the early developmental period

D: Symptoms cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of current functioning

E: These disturbances are not better explained by intellectual disability or global devlopmental delay

Severity of the above symptoms can vary, hence the notion of a “spectrum disorder”. It is graded in three levels, commensurate to the level of support required.

Further specifications include: intellectual impairment; language impairment; other neurodevelopmental, mental or behavioural disorder; catatonia; association with a known medical or genetic condition or environmental factor.

The Autism "Triad"

The triad of impairments is as follows, with some overlap between each:

– Communication: difficulty in expressing needs, emotions, feelings; impaired language development; understanding prosody; rigid speech patterns

– Interaction: issues with personal and social boundaries; self/other differentation, turn-taking; verbal / non-verbal cues; making eye contact; developing and sustaining relationships

– Social Imagination / Restricted and repetitive behaviours: self-stimulating (“stimming”), repetitive behaviours to the exclusion of others and lacking play, exploration and imagination; ‘excessive’ focus on particular themes/topics, inability to take on different perspectives or others’ emotional states and intentions

Stigma and Benefits around Diagnosis

There are multiple possibilities why an ASD diagnosis might not be sought:

– perceived social stigma – ignoring a problem

– feeling that not attaching a label to a child helps it progress better

– feeling of helplessness; as it’s a lifelong disorder with no obvious cure, there appears to be a lack of hope

– lack of support in local area

– time taken to obtain a diagnosis and cost of doing so privately

Better outreach can help address all of these and ensure personalised and adequate care for all.

A formal diagnosis can provide the following benefits:

– self-acceptance: following persistent personal difficulties, reduced self-blame

– acceptance by others

– extended support, both in school and workplace

– extension of rights under the Equality and Mental Health Acts

– access to benefits and other care provisions

– access to long-term care

– access to education resources (SEN)

Brain Differences in Autism

There are some detectable brain differences in people with ASD, including structure and connectivity. These include:

– Brain volume trajectory: ASD brain volume growth appears accelerated, particularly in the frontal and temporal lobes, in early children around two to four years of age. Adults on the other hand appear to show decreased volume or no difference, and it is thought that growth is arrested after around 10-15 years or age. Led by an accelerated expansion of the cortical surface before the age of two, without concomitant increase in cortical thickness, this expansion of gray matter appears linked to lower maturation of the cortical white matter, giving rise to atypical connections.

– Specific cortical regions have been suggested as being responsible for the various symptoms exhibited as they relate to language, social attention and behaviours, and repetitive and restricted behaviour, while accepting their heterogeneity.

No two brains are are the same, and this holds true for ASD in particular. A qEEG-brain map can show areas of dysrhythmia that could benefit form training in a personalised approach

– Enlarged amygdala in autism, specifically a subregion responsive to both salient stimuli and threats. The amygdala is a key subcortical element of the limbic system with strong links to certain cortical sites. We can train these cortical sites with neurofeedback.

– Grey and white matter volumes as well as gyrification in various brain areas are different in autism, including those involved in face and object recognition; intention of others; spacial awareness; internal organisation; language and expression of emotion.

A brain map can help personalise the neurofeedback training. With Neurofeedback, we can also train the white matter tracts.

Sensory processing and integration issues arise from dyrhythmia, or immaturity, of specific brain regions. Differences can include:

Auditory – discerning between background noise and relevant sounds; distraught or comforted by loud noise; attributing emotional content to sounds (or not); immersion in or ignorance of soundscape (comfort)

Visual – foveal vs. peripheral sensitivity variations and focus; colour perception and attributable comfort / pleasure / distraction; depth rendering; movement cognition; light intensity; scene construction / disjointment; temporal prediction error in moving scene

Tactile – touch sensitivity; association of pleasure with touch; pain threshold (harm alertness); predictability of touch, e.g. randomness of water flow / washing

Olfactory – general sensitivity; extreme association of reward / disgust with smell; distinction and its subconscious impact on social affinity, reward assessment and even dopaminergic (motivational) effects

Gustatory – sensitivity to taste and texture (spicy vs. bland), effect on food intake, extremes e.g. pica (craving non-food ‘taste’); strong links to olfaction and visual appearance. Dietary preferences can be guided by gustatory, visual, olfactory and tactilesensations, as well as their combinations / interplay; rewards in one sensory domain can help overcome aversion triggered in another; e.g. finger food arranged in familiar patterns can help overcome a dislike for the food-type (e.g. vegetables) in question.

The vestibular system helps us detect the position and movement of our head in space, and thus contributes to coordination of movements and posture, including our sense of balance. Hyper- or hypo-sensitivity in this system results in lack of balance, or the need/desire to stimulate it by creating movement (e.g. spinning, hyperactivity).

Proprioception is our sense of where we (our body) are in relation to other objects, space in general, and parts of our body. Hyper- and hypo-sensitivity results in clumsiness, misjudgments, invasion of personal space, pressure regulation and possibly writing; and stimulus-seeking, excessive movement and contact, and the application of weighted clothing, respectively.

Neurofeedback for Autism

With neurofeedback training, we can address the following manifestations of autism as there are specific brain areas responsible for each of the following:

– sensory processing and integration: visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, gustatory

– sequencing and planning of actions

– motivation and mood control

– awareness of surroundings and consequences of actions

– fear, anxiety, dissociation and detachment

– impulsive aggression and rage

– self/other differentiation

– verbal and non-verbal communication; speech and language

– auditory hypersensitivity

– rigidity of thought and expectation, inflexibility

– repetitive restrictive behaviour

– vulnerability caused by excessive recruitability (“being too nice”)

– motor function, mobility and coordination

– empathy and emotional understanding of self and others

– sense of self

– social boundaries

– dissociation, detachment and the feeling of needing to mask behaviour

– focus, concentration and organisation

– sleep: onset and quality

Neurofeedback for autism is a non-invasive, medication-free complementary therapy. It is safe, evidence-based and effective. Moreover, it is an enjoyable process that simply involves watching movies or YouTube clips – feedback to our brain is merely audio-visual, as small changes in volume and picture size provide the brain with enough information to mature its behaviour patterns.

Personalised Brain Training respects neurodiversity. With a brain map, we identify areas of cortical immaturity and train these. As such, we can improve group-minded thinking and the ability to thrive while preserving individuality.

Sensory processing is a well-researched process that involves many dedicated brain areas, and their interaction to produce an impression of our environment, and how it relates to us. Higher integration of ensuing awareness leads us into the realm of “what is consciousness”:

Science shows that our brain is engaged in a constant process of modelling, or predicting, our environment, both with regard to space and time. It does so on the basis of previous sensory information, as well as recent and consolidated memory. Predictions are then matched with reality, and the process begins again. This is an important distinction from the idea that we are merely reacting to our sensory input. It introduces the theory that we essentially anticipate the next moment, and then update our model of our environment, continually.

Autism can be viewed as an impaired capacity to efficiently engage in this predictive process. The theory easily explains the insistence on sameness and inflexibility with regard to changing routines, embracing novelty, interacting with moving objects, reduced appreciation of humour and even Theory of Mind, which is essentially the creation of a model of another person in one’s own mind. An unpredictable world becomes overwhelming, explaining the fear and anxiety we so often witness with the condition, and resorting to self-stimulation (stimming) is an anxiolytic response. As a result of reduced modelling and predictive capacity, repetition is favoured, and this can turn into a strength as replicative behaviours enhance certain skills or narrow areas of focus.

Again, there are neural correlates for this. Our Default Mode Network (DMN) is a set of brain areas that constitute our neural basis of self, and is preferentially activated when we are engaged in self-reflection and imagination. In awake state, we oscillate between activation of our DMN and our Task Positive Network (TPN). In a mentally healthy, neurotypical person, the correlation between their respective activation is anti- or counter-cyclical, meaning that when one is active, the other is not, and vice versa. In ASD, this segregation is impaired, as well as the within-network integrity of the DMN. This is a connectivity issue rather than lack of tissue – the ASD brain enjoys a faster growth during its first year, and results in a 2-4 year old ASD brain being no different from a neurotypical adolescent or adult in the majority of cases.

Traditionally, we would think of our TPN as being reliant on sensory input. However, REM sleep is an example of intense DMN DEactivation, and hence TPN activation, yet in this stage we are not actually taking in sensory input. This shows us that our brain generates its own interpretation of reality, and in the extreme (sleep) can do so without resorting to cross-checking with sensory input. The fact that REM sleep is our prevalent condition from at least week 23 / 3rd trimester through our first year of life is testament that consciousness does not explicitly depend on external input. Our perception of reality is self-generated, almost like a simulation. This predictive capacity is likely impaired in autism.

With neurofeedback, we can train our Default Mode Network, and its connectivity with our sensory systems. This leads to improved feeling of ‘groundedness’, sensory integration and synchrony with our environment. When we train sensory processing sites, we are strengthening our Task Positive Network. There are training protocols that reward efficient transition, and neurofeedback training on the whole improves our predictive capacity and hence general flexibility and sensory integration.

Autism Legislation and Advocacy

UK Mental Health and Equality Legislation

Current UK legislation and guidance with regard to autism is as follows; the acts outlined put responsibility on public services in a forward-looking, anticipatory manner, and provide resources to accompany them through their life to avoid harm and further self-empowerment, thus preserving dignity and life itself.

2009 Autism Act – requires the government to introduce and keep under review an adult autism strategy, implemented partially by local authorities and the NHS; this resulted for example in 93% of areas in England now having an adult diagnostic service, with over 50% not having one before 2009

2022 Health and Care Act – introduced a legal requirement for all health and social care services registered with the CQC to provide employees with training on autism and leaning disabilities (“Oliver McGowan Training”, after a Bristol boywho died age 18 in 2016 who was given anti-psychotic medication Olanzapine and suffered simple partial seizures while in care and ultimately died of pneumonia and hypoxic brain injury, caused by Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS), an adverse effect of Olanzapine, though the coroner concluded that Olanzapine had been properly prescribed; the family believe that the hospital did not meet Oliver’s needs on arrival through chemical restraint, thereby increasing his distress, in contrast to the coroner finding the care which led to his death was “appropriate”)

Mental Capacity Act 2005 – provides five principles for the protection and empowerment of people who may lack the mental capacity to make their own decisions about their care and treatment over 16 years of age; these include a presumption of capacity; support for making their own decisions; increased flexibility of perspective on “unwise decisions”; a duty to act in their best interests; and a requirement to provide the least interference with the person’s rights and freedoms of actions, assessing particular circumstances.

2010 Equality Act – places a requirement on UK public services to anticipate and prevent discrimination against people with disabilities, including people with a learning disability, autism, or both

The 2010 Equality Act also pertains to the avoidance of discrimination in schools and places of higher education; SEN (Special Education Needs) support extends to progress checks and assessments to affected children under 5; special learning programmes, extra help from assistants and physical / personal care to the age of 15.

Under the Mental Health Act (1983, updated 2007), an Independent Mental Health Advocate is to be supplied to anyone detained under this Act, and they have a right to a Care Act advocate, supporting people with issues relating to their mental health care and treatment.

Promoting the Rights of Persons with ASD

Examples how the rights of individuals with autism can be promoted:

– knowing and understanding existing legislation and guidance relating to autism, mental health, disability and equal rights, and acting on these, such as implementing person-centred care

– taking a critical approach to media reports on autistic persons, understanding generalisations and pointing these out to others, including directly back at the press, as well as around others who might not be aware of this

– challenging discrimination and taking a pro-active stance in implementing the guidance and legislation, as this is ‘alive’ and depends on general awareness and accurate and appropriate actions

– enabling the person with ASD to be directly involved in conversations and decisions pertaining to them, and helping to avoid unnecessary intermediation

– supporting advocacy groups and promoting further causes that keep the momentum going, as previous milestone legislations have shown.

Every person on the autism spectrum is different, with regard to abilities, needs and goals, so to comply with the person-centred approach (and the Mental Capacity Act), as well as the general goal of compassionate, human interaction, a carer needs to understand the individual’s point in their path, how far they’ve come, which goals have been set by them and their team, and what position they are in at the present time to pursue that path. Achieving one’s potential is an important part of developing a healthy sense of self and having a good quality of life, while also providing a positive feedback loop that can help mitigate many other challenges they are facing as a result of the comorbidities of ASD, both mental and physical.

Person-Centred Support for Autism

Person-centred support focuses on care on the needs of individuals, ensuring that peoples’ individual preferences, needs and values guide clinical decisions, and providing care that is responsive, tailored and respectful to them. It was developed in partnership with Skills for Health and Skills for Care, and sets a framework to share best practices that can be implemented by various care segment, such as health, social, housing and local authorities. It is a framework launched in 2018 involving engagement, relationship building skills, delivery of training, education and learning opportunities, and identifies enablers to further this cause.

It is important to treat an ASD person as an individual because:

– everyone deserves to be treated with dignity and respect, and that crucially involves recognising their individuality, with respect to values, needs, goals and care

– people with ASD are, as the name says, on a spectrum, and therefore exhibit individually different needs and challenges. These can range from intellectual, social, communication, physical and emotional, and each person’s manifestation of their blanket “ASD” diagnosis is different.

This also ties in with the person-centred approach described above, with the goal of preserving their dignity on a human level and compliance with the various legislations also described above.

Compassion & Non-Judgment

Some examples of providing support that is compassionate, that is, maximises emotional support in a dignified and constructive way, are active listening, respecting personal boundaries, applying interpersonal techniques such as sitting next to someone who avoids eye contact, instilling hope, having appropriate humour, being optimistic, not getting demoralised, being creative, and generally appreciating someone as equal and human.

Being non-judgmental in one’s approach to care and support involves seeing the other person as equal and human, having a respectful attitude without sense of hierarchy due to perceived abilities; seeing more in the person than their current state might suggest and bringing out the best / maximising their potential; and respecting choices that might appear “unwise”.

Managing Behaviour in Autism: Strategies

Certain behaviours might be responses to a form of sensory overload, and not obvious to spot / make sense of until better empathising or getting to know the individual and assessing the context in which they resort to the behaviour in question. They might be self-protecting, or conditioned into achieving something this way when there are other alternatives that can be taught.

Proactive strategies are pre-emptive, and so applicable when a situation is predictable or known; this can help reduce sensory overload, prevent undesirable consequences and condition positive responses; it may also not work when conditions change surprisingly, and it doesn’t necessarily teach flexibility or adaptation, as well as being possibly over-protective and risk-aversive.

Reactive strategies are generally de-escalating and necessary to avoid harm/self-harm, but as a result of being unforeseen, they might be sub-optimal, not teaching the right behaviour and can be seen as unpredictable and hence hostile by the ASD individual.

Approaches to support positive behaviour are positive reinforcement (operant conditioning); generally rewarding self-initiated, constructive actions; creating environments and subtle (fading) prompts conducive to such behaviour; generally explaining positive and negative behaviour; abstracting this concept gradually to induce internalisation of a thought construct that encourages self-derived positive behaviour; doing so in the context of practical, novel situations to stimulate flexibility and creativity

Communication issues can cause isolation of self and feelings of hostility / misunderstanding by others.

Social skills can impact perceived empathy and further exclusion.

Repetitive, restricted behaviour and likewise result in exclusion and self-absorbtion.

Behavioural challenges can cause harm to others and self.

Generally unpredictable and wrongly interpreted actions can increase stigma and discrimination.

Rule and process adherence can preclude novel experiences for self, and increase burden on carers.

Distraction from the triggering situation; substitution with something enjoyable; positive reinforcement through a compassionate and insightful approach; providing a safe and stable environment, which can often be induced by the presence of someone they trust

Providing respite to be able to regain perspective, and hope; showing empathy and compassion towards them; joining groups with other parents to share experiences and reduce feelings of guilt, stigma and isolation; keeping a temporal perspective by keeping a diary and noting achievements and improvements.

Autism in the Workplace

Rights of ASD individuals with regard to accessing services and facilities have been established through various legislations already outlined above, and repeated here:

Autism Act 2009: specifically requires local authority and NHS to provide access to ASD individuals

Equality Act 2010: prohibits discrimination in such services and facilities

Special Educational Needs and Disability Act 2001: protects rights of students with disabilities

Mental Capacity Act 2005: upholds rights of individuals with limited decision making capacity to make decisions in their best interest / self-determination

People with ASD can be at a disadvantage in competitive workplace environments due to:

– lack of self-confidence and assurance in their relevant skills

– inflexibility when assessing requirements e.g. in ads regarding their suitability

– general and intrinsic discrimination, real and perceived

– difficulty in managing the interview process regarding personal interaction

– general feeling of overwhelm, lack of obvious precedents and role models, paucity of mentors and support while in the job and with regard to creative career management

– not being able to realise transferability of their skills and underestimating their ability to adjust and adapt

– general lack of encouragement due to labelling and stereotyping

We can provide support by:

– finding suitable courses and training events

– presenting these with the goal of enabling the person to make their own decisions (‘coming from them’)

– researching the providers, meeting the teachers, preparing them in advance to enable them to establish quick rapport

– encouragement and promise of reward for attendance

– ensuring attendance

– collecting feedback from provider and teachers

– making sure there are lines of communication at all times and the person doesn’t feel abandoned

– ensuring safe return

– finding appropriate and interesting activities

– conveying these while respecting choice and self-determination

– making transport and attendance as easy as possible

– ensuring attendance

– setting objectives and understanding of the growth opportunity

– positive reinforcement of independence

– liaising with the employer, preparing them for any perceived peculiarities, adjusting the work environment per above

– facilitate initial and repeat attendance logistically

– providing continued encouragement, dwelling on positives and progress, addressing concerns, conflicts and issues and helping resolve these proactively with the employer

– managing the induction process (‘first impressions count’, on both sides)

– general preparation for the ‘unknown’ and reassurance of continued support

– continued encouragement and workplace liaison as above

– communication and management of any problems, issues and difficulties

– ensuring a support environment at work, including HR, mentors, introduction to other employees

– manage the review process, ensure communication is constructive and supportive

– ensure fairness and maximise potential with regard to career prospects

– provide support in the event of challenges, failures (real and perceived), and interpersonal relationships at work

Neurofeedback is a form of complementary therapy and should not be seen as a replacement for conventional medicine. qEEG brain map-based neurofeedback training takes a more holistic approach to brain functioning, rather than just focusing on medical symptoms. It is not intended as a form of diagnosis nor medical intervention nor medical advice per the disclaimer.

Neurofeedback is a form of complementary therapy and should not be seen as a replacement for conventional medicine. qEEG brain map-based neurofeedback training takes a more holistic approach to brain functioning, rather than just focusing on medical symptoms. It is not intended as a form of diagnosis nor medical intervention nor medical advice per the disclaimer.