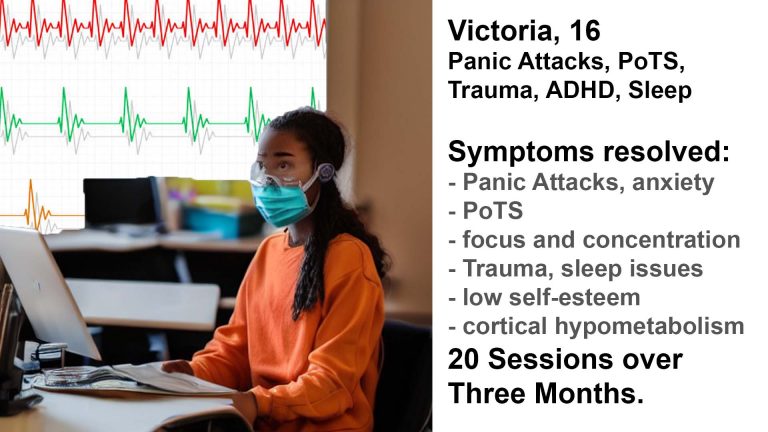

Case Study: Victoria, 16, Panic Attacks, Trauma, ADHD, PoTS

Panic Attacks, PoTS, Anxiety and Sleep Issues resolved in Three Months

Before

– Panic Attacks, anxiety

– Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (PoTS)

– Focus and Concentration Issues

– low self-esteem and motivation

– sleep issues

– cortical hypometabolism

– fatigue

– trauma markers

Twenty Sessions, over 3 Months

After

– PoTS symptoms, panic attacks resolved

– improved focus and concentration

– resumption of school studies, excelled in mid-terms

– restorative sleep

– much improved self-confidence

– healthy cerebral blood flow, some corpus callosum issues remain

– healthy detachment from invasive mother

Victoria's Full Story:

Victoria, 16, was experiencing panic attacks at the end of August, just before her junior year of school (year 12) was about to begin. Hyperventilating, she was scared of her body’s overdrive, necessitating an A&E visit at 3am the night before her first day back. Having spent much of the summer vacation isolated at home with her family, who a year post lockdowns was still exercising social distancing, she had been looking forward to socialising again, meeting her friends and embarking on the critical last two years of school.

Some anxiety had been building up due to her difficulties in absorbing written information in a timely manner, as well as when writing essays, which would take her substantially longer than her peers. A homework assignment that should take an hour to complete would require four hours of her concentration, which would have taken a toll on her ability to socialise, though this aspect was masked by the family’s strict self-isolation protocols during the previous two years. Once submitted, she usually achieved top marks, and her intellect and potential was apparent. In Biology, a subject she aspired to study at higher level, her teacher gave her coursework in advance of the new school year to complete in view of this unexplained condition. When she discovered how long this was taking her to do, the prospect of falling behind within a month instilled deep worry that weighed on her. Things came to a head however the night before school started, and her body felt out of control.

The doctors prescribed mild sedatives (beta blockers) and gave her a bag to blow into so as to help normalise her breathing. This helped and became an important habit before and after school during the first week of term. Her mother was still requiring her to wear a N95 (FFP2) face mask continuously during the school day out of fear of Covid contagion. Victoria’s sister had recently started neurofeedback training for her depression and self-harm inclinations and was experiencing great results, while appreciating the non-invasive character of the treatment – no soul-searching talk sessions with a psychotherapist of the mother’s choosing, just watching her favourite new movies. Victoria elected to start neurofeedback training on her third day at school, and we began with a brain map and two sessions per week.

Victoria’s brain map confirmed the pleasant core aspects of her character – emotional insight, a caring demeanour, desire to integrate and form social bonds, and the ability to take on different perspectives. She also had multiple sources of anxiety, some trauma markers, a sense of hypervigilance and guilt, overpriming her environment at the expense of her own sense of agency, and sleep, focus and mood control issues. Most worryingly, her brain appeared to be hypometabolised, meaning, lacking necessary blood flow in many critical areas, and a clear hemispherical division, that is, a lack of connectivity between the two brain halves, in virtually all functional areas.

Having received medical attention frequently during the preceding months, the blood flow issues and structural findings of the brain map had not been flagged, and her mother took her to a neurologist for further investigation. By this time, her panic attacks were more manageable yet Victoria had developed a deep sense of distrust in her bodily function, convinced something was wrong with her. When she got up from her seat, her heart rate would frequently explode, and by her mother’s measurements and research, she could easily have met the diagnostic requirements for PoTS, or Postural Tachycardia Syndrome. The neurologist would have none of this. At the time, PoTS had not received much mainstream coverage, and itself appeared to be a fairly novel, yet real, condition. He explained to her that what she was going through was mere psychological anxiety, or “somatisation”, and found no grounds for concern in his scans. Nonetheless, physical exercise, even short walks, remained unworkable – a travesty for an otherwise healthy young teenager.

Victoria had a history of sleep deprivation and early trauma. Adopted during infancy, her new parents took her on a trip to her country of origin when she was seven, and she was subsequently unable to sleep properly most nights, lying in bed with her eyes closed yet her mind racing, all night. This had only improved a few years prior, though she had never recovered the energy and vivaciousness of her early years. She had also changed school three times as a consequence of racially motivated bullying, together with her sister, and her mother had developed a paranoid cynicism that preceded all social interactions, as if to purposefully conjure up antagonistic reactions in an attempt to prove the worst and thereby achieve some sense of control and certainty. Her mother’s combative approach contrasted with Victoria’s, and her sister’s, gentle and likeable demeanour. The two girls’ friendships at school were carefully vetted, and their mother’s presence was felt in every fibre of their lives. Team sports were discouraged, and class trips prohibited. Birthday parties were curtailed after disappointments in their early years, and the family’s isolated lifestyle made meetings with friends outside of school hours rare and difficult. Instead, the family engaged in weekend activities together, comprising music lessons, art and theatre appreciation, and outings to nearby parks. Privacy from their parents was an impossibility, and in fact their mother, who had given up her own career, declared her increased devotion to “be there for them completely” during their important final two school years.

Victoria did two neurofeedback sessions per week for the first month of school, and improved significantly. Her panic attacks subsided, and her PoTS symptoms were manageable, though she still felt lethargic on the weekends. The social side of school was emotionally invigorating, and her mother developed a new fear about the teenager’s natural interests. At this point, Victoria had been made to share a bed with her distrustful and concerned mother, whose overwhelming presence had taken a toll on her marital relations, with her husband relegated to a separate room. Victoria’s sister meanwhile prospered socially and academically, enjoying the relief of reduced maternal attention. Her mother took to the idea of reducing the academic pressure on Victoria with typical fervour, contacting teachers regularly, and she was exempted from completing homework assignments and left to work at her own pace. Victoria’s concentration had improved concurrently, a trend that was set to continue over the next months and culminated in passing her mid-term mock exams with good results, including biology that had triggered the initial episode.

For the next month, we did weekly neurofeedback sessions, followed by a brain map after the twelfth session. The hypometabolism had largely resolved and interhemispheric connectivity impressively occurred. Marked sleep improvements were corroborated, as were reduced anxieties. PoTS symptoms were no longer mentioned. Motivation had increased, and the moving body pain was manageable. Victoria felt able to complete her homework assignments, and school became a priority for the next month in preparation for her mock exams. We did two more sessions and took a break from neurofeedback.

Shortly before Christmas, Victoria’s mother sought to resume neurofeedback training. Victoria had done well in her mock exams and was coping with schoolwork – the initial issue of taking much, much longer to complete assignments than her peers was no longer mentioned. Neither was PoTS, headaches or sleep issues. Mask wearing, the N95 type, was still enforced by her mother, who did not entertain the idea that this could infringe on her ability to socialise or learning how Victoria’s facial expressions and reactions could impact those around her. In addition to this censorship, her mother’s stated fear of Covid resulted in further constraints on social interaction, with the prospect of spending her birthday alone at home over the pending vacation. Due to the six week gap since our last session, we started with a remap, which unfortunately showed some regression. There were clear trauma markers, some anxieties came back, as did her hypervigilance, and in addition to a worrying lack of own perspective, a marker indicating the presence of an abuser, or someone Victoria paid particular attention and monitoring capacity towards, appeared for the first time.

Victoria’s mother had spent the first term of the school year under severe stress, committing herself fully to support her adolescent daughters, and inserting herself further into every fibre of their lives. She acknowledged that this was in stark contrast to how her brother managing his children’s transition into early adulthood. Her own sleep had not been great to start the term with, and the built up worry, anxieties, and pre-existing mood control issues were exacerbated by the stress. Afraid of losing control, and the pending next stage of her own life once her children were going to go to university and leave the house, she compensated with surrendering any own motivations to perceived helpfulness and dedication. Scheduling every move and activity, she noticed when Victoria was spending time locked in her room, or even the bathroom in their weekday home where she was sharing again with her sister. Any semblance of a social life from before Covid lockdowns had long gone, and she was feeling neither part of general society nor connected to former friends and family. She was ever more convinced of intrinsic racism and antagonism towards any of her causes, and complained about the abolition of social distancing and other Covid measures that had happened over a year ago by now. Her overbearing intensity was difficult to dispute, and it appeared that her children, and husband, were suffering from her lack of self-insight. She would frequently break down when out of sight of her children, upset when her husband, himself suffering from Long Covid symptoms, found the occasional energy to call her ‘neurotic’. It would take a year for her to commence neurofeedback training for herself (see Case Study).

We did a one-week intensive training, with one (long) session per day, over the course of a week, which provided significant relief throughout the social void of the vacation period. When school resumed, Victoria was back in her element.