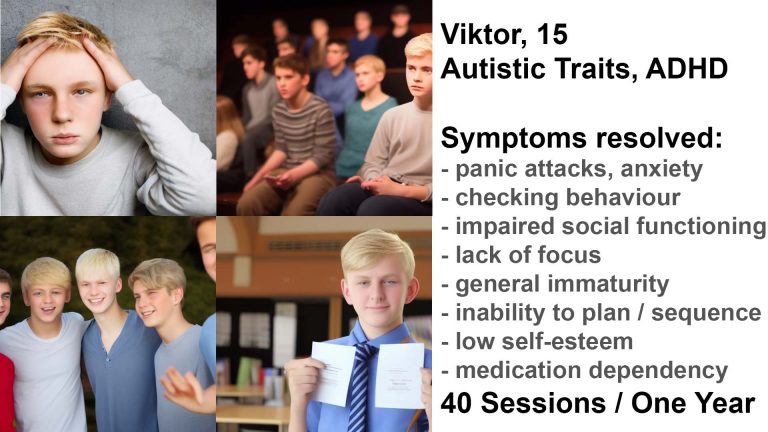

Case Study: Viktor, 15, Autistic Traits, ADHD

Autistic Traits, ADHD, Panic Attacks, Tics and Medication Dependency resolved in a Year.

Before

– anxiety, panic attacks

– checking behaviour

– impaired social functioning, loner qualities, bullied

– mild repetitive, restrictive habits of self-regulation

– inability to plan / sequence study, independent time management

– lack of focus, highly distractible

– substandard academic performance

– delusional views of self-realisation

– immature understanding of social boundaries, social emotions

– polarised thinking

– adherence to routines, eating habits

– tics

– low appetite for risk, exploration and novelty; fear of unknown

– low self-esteem

– stimulant medication dependency

Forty sessions, over one year

After

– cessation of stimulant medication

– panic attacks stopped

– formed close circle of friends

– strengthened sense of self, realistic plans for future

– checking behaviour minimal

– tics abated

– focus, motivation, sequencing ability greatly improved

– initiative and sense of being part of community

– able to take on different perspectives, reason

– improved flexibility

– maturity leap from child to adolescent

Viktor's Full Story:

Viktor was 15 years old when his parents became extremely concerned about his ability to start the school year at his boarding school. About to enter year 11, or 10th grade, he would be due to sit his GCSE exams that are hugely important for university application. His self-confidence was decimated; he was suffering frequent panic attacks; engaged in checking behaviour regarding fire safety and other hazards; felt unable to socialise, even with familiar persons; and his constant anxieties were a burden on him and his parents.

Viktor had a history of mental health issues and his mother engaged both a psychiatrist and life coach since he was nine years old. Diagnosed with ADHD at this early age, he was prescribed stimulant medication, which had initially boosted his confidence and raised his academic performance substantially; however the positive effects had abated in recent years as his grades slumped, confidence eroded and the (low) dosage was maintained. Recently, his anxieties had worsened and evolved into incapacitating panic attacks; he also frequently felt that people around him were talking about him. Viktor was found to have three out of five assessed autism symptoms:

- Deficits in social functioning: Victor appeared oblivious to social boundaries and conversational cues, masked in part by shyness and hypervigilance, especially in unfamiliar surroundings. His friendships were limited to peers he had grown up with and who were now in different schools, and on steeper academic trajectories that widened the gap in their interests and ambitions; at his boarding school, he showed loner qualities despite social encouragement from his housemaster and activity organisers

- Mild repetitive, restrictive habits of self-regulation, such as resorting to playing console games for hours on end despite every effort to present him with social engagements and activites; and a hyperfixation on following his favourite sports of basketball and football (soccer), a motivation and interest that did not translate into any other subject areas, including school

- Inflexibility with regard to changes of plans and daily routines; a need to understand exactly what new experiences such as travel and activities would entail, accompanied by a low appetite for risk, exploration and novelty; exacting requirements for food choice, preparation and presentation, for example having to clearly separate vegetables from meat on his plate, and limited options; and a complete lack of ability to sequence, plan and anticipate future developments, from daily time management, which was compensated by a tight school and after-school schedule with tutoring; to career choices and consequent school options, which contrasted starkly with his younger brother.

To his mother, Viktor appeared to be living in his own fantasy world. He was not learning essential living skills, which was not helped by possibly excessive attention and servants at home catering to his every need. Her ambition for him to follow his father’s footsteps in attending a prestigious US university and becoming a successful banker seemed far removed from Viktor’s lack of vision and engagement with his environment. The immediate disconnect however materialised in his parents’ concern that he felt unable to commence this crucial school year.

A few weeks into his first term, we began neurofeedback training with a brain map and a first session on a Saturday, as he had chosen not to take part in weekend activities at school and preferred to return home. His brain map confirmed many of the traits above, and showed other vulnerabilities. Of particular concern was a sense of feeling sensory overwhelm that contributed to his rigidity of thought. He mentioned that he felt that at times he thought people were talking about him, when in fact they weren’t. Various trauma markers showed up, as did social and general anxieties, mood control and motivation issues, severe distractibility, personal space and social boundary issues, feelings of guilt and a lacking sense of self-worth, organisational and executive deficiencies, self-absorbtion and tendency to prioritise internal content, a lack of sense for the intention of others and an active, unfulfilled search for being part of a group or greater cause. Structurally, his brain had developed soundly and in line with expectations, which was encouraging.

Viktor enjoyed the neurofeedback sessions, glad that he didn’t have to talk, and chose light comedies and series such as “Friends” and “Ted Lasso”, which he could watch for two hours at a time. He began feeling calmer and more self-assured. After the fifth session, his mother expressed concern that his panic attacks had not subsided, occurring especially when left to his own devices. Viktor was still taking stimulant medication prescribed for his ADHD diagnosis, and in consultation with him and his psychiatrist, he agreed to stop taking it, particularly as he felt they were no longer of any benefit to him. Within two sessions, his anxieties had dropped immensely and he reported no further panic attacks. It is noteworthy that a brain map after the tenth session showed a remarkable change in his ability to take on different perspectives and proneness to relational thinking, or the sense that everything is directed at oneself, which can be a precursor or constituent of psychosis. We will never know whether it was the stimulant medication in the first place that instituted this vulnerability, and/or whether neurofeedback training made him more sensitive to the medication and thus helped him transition off it.

By mid-term, Viktor expressed that he “felt really good about myself”, and the family trip abroad went well, without the expected fallbacks. He also enjoyed a much daunted school trip, getting to know other peers from different classes. By Christmas, he felt free from anxieties and of particular note, had established a circle of friends at boarding school that gave him confidence and a sense of belonging. He started to remain at school some weekends, joining the tennis team and other extracurricular activities. Viktor’s parents were delighted by his emotional progress. In parallel, it was noticeable how Viktor was maturing emotionally, exemplified by his choices of movies, and comments on their content and plot developments. He asked his parents to talk him to theatre performances during this time, and was commended for his performance and initiative in his school drama class.

Viktor’s academic performance however had been lagging for some time, and the mock-GCSEs before his mid-term break produced atrocious results. His mother was panicking, and his father upset. Provided with every tutoring resource, Viktor appeared not to be able to manage his own time, and although his tutors reported a new level of focus they had not seen in him before, this was still conditional on substantial guidance and ‘warm-up’ in each session. It seemed that he was not provided with guidance and micromanagement of his self-study time, nor did Viktor seem to feel accountable for his performance. A plan was instated to help him structure his self-study – previously there was no such coordination – and sanctions on his game console use.

Viktor’s tics had returned, as had happened previously during times of intense stress. While barely noticeable before, he was now conscious of them and this gnawed at his self-confidence. We included training protocols that saw these abate within two sessions.

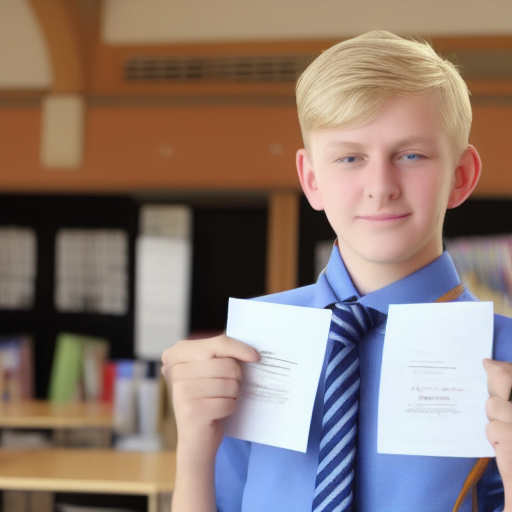

We continued with neurofeedback training from January through May, managing Viktor’s natural anxieties regarding the upcoming exams, as well as working on sites relating to focus, distractibility, motivation and sequencing of actions. His tutors found that this worked – Viktor was studying more effectively by himself, and his attention and interest in subject matter were transformed. GCSE exams are spread over the course of a month, and his mother was happy with his mental state, stating that he was “in a good space”. Viktor seemed to hold up under the pressure, and made sure to integrate as much sports and activity into his limited free time as possible for balance. Self-regulation with excessive console games had become minimal. His parents were optimistic about his prospects, and organised an internship for him over the summer.

During the last week of exams, with the internship looming, Viktor fell out with his father. Their relationship had never been close, as Viktor felt a sense of pressure and expectations he couldn’t live up to. Suddenly, checking behaviour he had not shown for many months reappeared, and he had difficulties falling asleep. The upcoming placement became a daunting prospect, and his father became angry at his lack of enthusiasm, culminating in various confrontations. This contrasted strongly with the way Viktor had managed his exam period. We did three sessions before his summer vacation, which calmed him substantially and helped with the guilt and disappointment he feared to have caused. Viktor appeared to have been pushed too far by his father’s ambitions, stood his ground with respect to his desire, which was to relax and spend time with his friends after the stressful exam period, and asserted himself naturally. There was a noticeably stronger sense of self, and Viktor appeared to be a transformed person from the shy, in fact terrified, underperforming child he presented as less than a year earlier.

His maturity had improved substantially over the course of a year, and Viktor had transitioned from child to adolescent in an accelerated time frame. This was confirmed by before and after brain maps.