Simon, 19, Bipolar, Psychosis

Transformed in Two Months or 15 sessions

Simon is 19 years old. He had attended an elite boarding school as a day student on a bursary, meaning he felt socially excluded from his wealthier peers while being aware of his privilege. His mother had taken a controlling role in his education, choosing his university degree course, Spanish and Business, as well as any other facet of his life she could find. Simon’s father had been managing his severe Parkinson’s with implants and fentanyl since he was nine. Simon relished his first month at university.

Social and outgoing, Simon felt a new freedom. He took to the newfound social scene and acceptance overly well, and despite no drug use, experiencing a manic episode. Simon appeared to be friends with everyone and well-integrated. However, he was starting to experience panic attacks and severe lows after nights out. This rapidly transformed into paranoia and culminated with Simon being hospitalised (sectioned) within the first five weeks of university. He spent a month in a psychiatric ward and began taking psychotropic medication. He was diagnosed with bipolar depressive disorder and rehabilitating from psychosis.

When he was released home, Simon did not endorse the idea of returning back to uni, and was staying in his room, watching movies and gaming when he was not asleep. He felt generally monged, apathetic, and his self-confidence had eroded. Avoiding social contacts, he would easily get annoyed at his mother, or at times even the slightest things, yet he was not violent. His moods would fluctuate, and his focus was shallow. There were no projects that could interest him, and this continued throughout what should have been his first year at university. His mother was becoming increasingly concerned, as no medication was providing the necessary stimulus, and sought out complementary therapies. Simon had tried to stop taking Abilify during this time and found he could not do it – the physical withdrawal made his body shake.

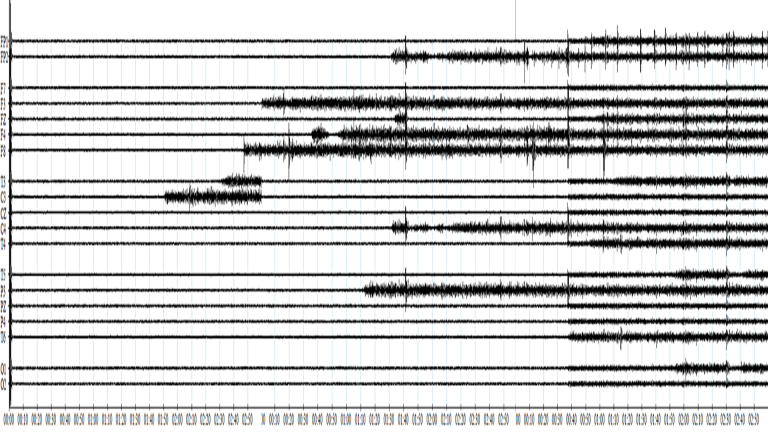

We began with a brain map. Having ensured all connections were good, the first recording was concerning. The signal was minimal, leading to a re-check that indeed, all connections were fine. After almost two minutes, a motor area signal became particularly active, and a minute later an adjacent site. Over the next three recordings, various sites ‘came alive’ in this fashion at different times, front, back, laterally, until after around seven minutes of recording time, all 19 sensors were showing healthy activity. This development was corroborated by spectral plots of activity by frequency, and the functional connectivity charts reflected a resolving general hypometabolism, with intra-hemispheric connections notably weak at first. There was no talking other than the minimal instruction “eyes open” and “eyes closed” for every three-minute recording, and no touch, only the presence of a new person in the room (myself).

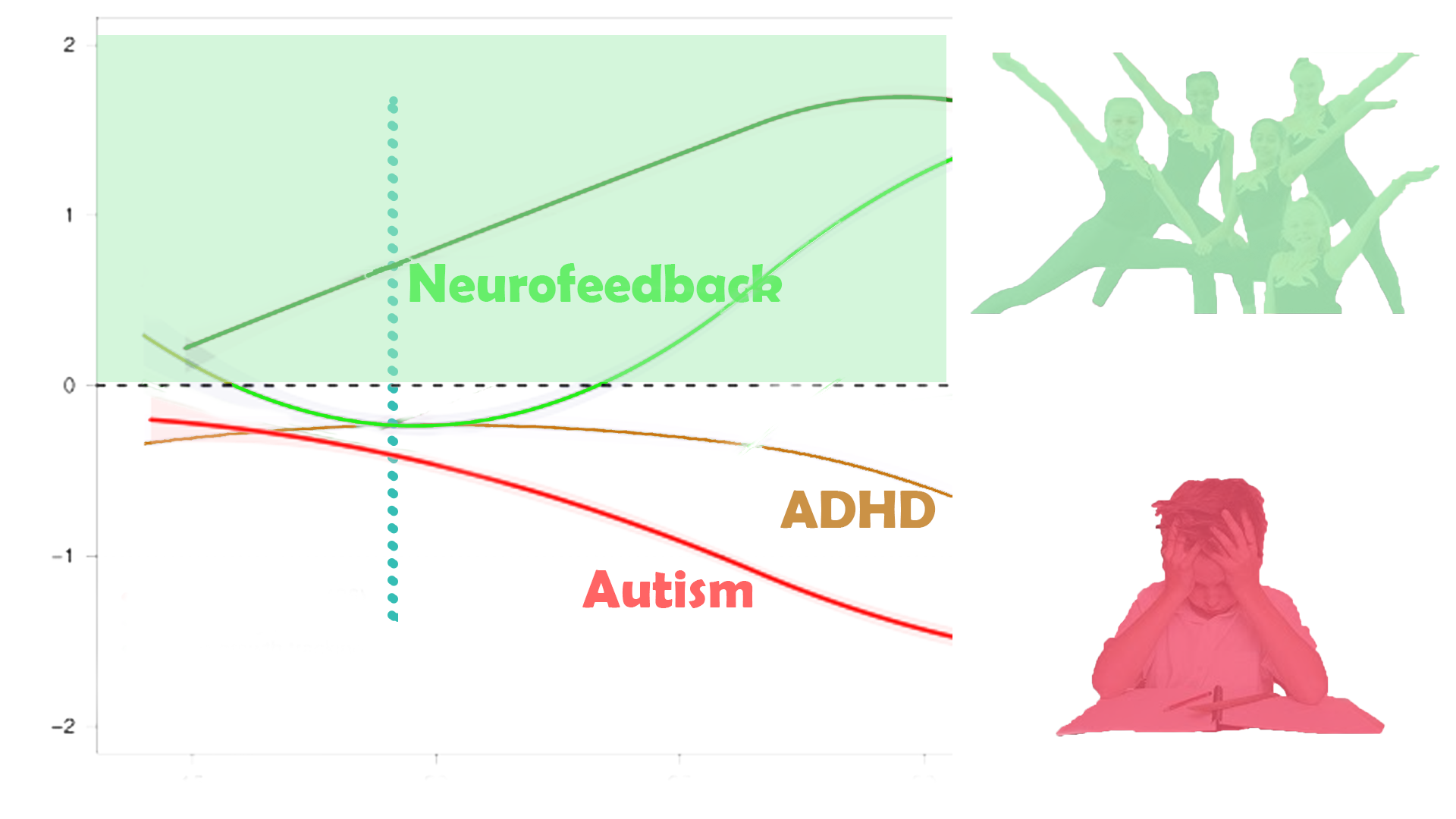

The brain map showed fluctuating indicators of vulnerability to psychosis, mood and physiological arousal control issues, trauma markers, distractibility, various sources of anxiety and hypervigilance, and an oversensitivity to perceived reputation or judgment. We began working on Default Mode Network and other relevant sites with neurofeedback training. Simon didn’t want to wear headphones and was comfortable with speakers that provided the sound to the movies, and with its slight and temporal variations in volume, the feedback for his brain. We were able to do 2.5 hour sessions, watching a feature film and some series each time; two sessions per week.

Initially, Simon felt as though he had just taken an exam, his head had gone through an exercise. He slept well and remembered dreams. Within two weeks, or four sessions, Simon felt more aware of his grogginess, a sign that the medication was too strong. In consultation with his psychiatrist, he was able to reduce the dosage, first in stages and then to the minimal amount he would tolerate. This proved successful, as Simon’s brain seemed less reliant on such numbing. The first five sessions he describes as a difficult time, a transition between shame and motivation. He looked forward to each of our sessions and enjoyed them, yet was left between hope and doubt after, an unsatisfactory feeling. It contrasted with the solid numbing of his usual rituals. When he saw that it seemed possible to reduce his medication, Simon reached a milestone. He continued to improve in many ways:

- Felt a clearer head, less brain fog, more focussed

- More motivated, started projects, study for resuming university

- Social, contacted former friends, started to play football (soccer) again locally

- More flexible in interactions with his parents

A further brain map confirmed these changes, and more. Within two months, we had transformed Simon’s trajectory and helped him reduce his medication to minimal levels. Fifteen sessions had changed Simon’s course from apathy to participation.