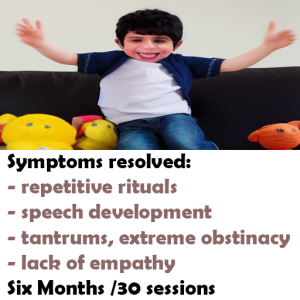

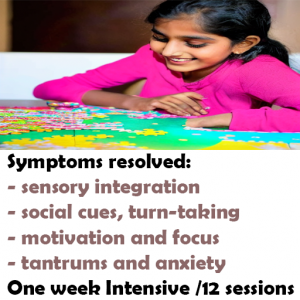

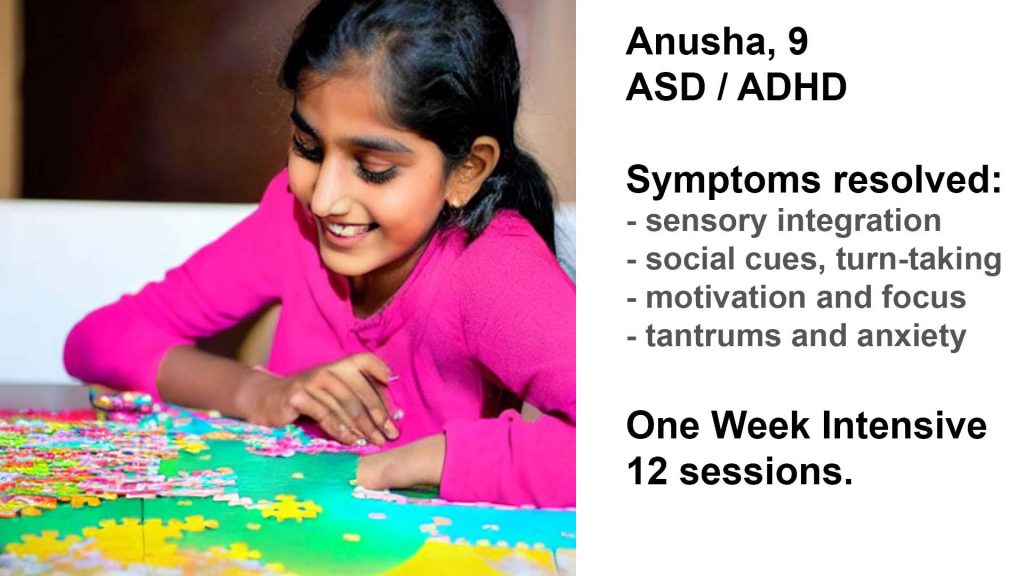

Case Study: Anusha, 9, ASD / ADHD

One Week Intensive to Resolve Autistic Traits

Before

Issues with:

– Impulsivity and rage control

– executive / social functioning: taking turns, social cues in conversations, interrupting, team-work

– sensory processing: scared of heights, loud noises

– squirming / rocking in seat since baby (“stimming”)

– focus and perseverance (giving up easily)

One Week Intensive: 12 sessions in 7 days

After

– Calmer, less explosive; didn’t “lose her rag” easily; already noticed this during the intensive

– spontaneously picked up a book and started reading; previously unheard of

– showed patience and persistence; completed a complex puzzle of own accord

– negotiated her way into a playgroup that previously ostracised her

– improved interoception and healthy assertiveness; explained why she didn’t want to continue an activity she was doing to please her parents

– substantially reduced anxiety and hypersensitivity to noise; no longer an issue

– persistent results after one month, and a year later.

Summary:

Anusha, a 9-year-old who had experienced multiple school changes due to an international upbringing, presented with behavioral challenges that seemed contrary to her intrinsic personality. Her parents, particularly her mother, a medical doctor, were pushing for a diagnosis and meanwhile sought an alternative approach for addressing her difficulties, which included sensory integration issues, social and executive functioning delays, distractibility, impulsive aggression, and anxiety.

Anusha did a one-week intensive neurofeedback training course in the UK during a term break. The initial session involved conducting a brain map, during which Anusha displayed a remarkable level of maturity and keenness to understand the process and its objectives. The map identified various vulnerabilities, including issues related to social understanding, impulsivity, aggression, distractibility, and fear.

The intensive training comprised twelve neurofeedback sessions in seven consecutive days, with Anusha enjoying two sessions of screentime per day, each lasting two hours. Her parents utilized the breaks for outings and to provide her with diverse international cuisines. Already, her mother noticed improvements during the training week, including increased calmness, better response to changes of plans, and a more rational assertiveness.

After returning to school, her parents observed significant positive changes in Anusha’s behavior, including increased calmness, patience, and persistence. Anusha also exhibited healthier assertiveness and improved interoception, allowing her to better express her feelings and bond more closely with her family. She successfully integrated herself into a schoolyard playgroup that had previously been hostile.

A follow-up brain map at the end of the week confirmed these positive transformations, and her brain’s structural maturity metrics had also improved. Following these positive outcomes, Anusha’s mother had originally intended to continue neurofeedback training during the summer vacation. However, a psychiatric assessment conducted a few months later did not find grounds for an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnosis. Anusha felt accepted and motivated in her school and after-school environments, and the family chose to spend their summer vacation at Disneyland instead. The intervention was successful in bringing about positive changes in Anusha’s behavior and overall well-being, contributing to her improved social and academic experiences.

Anusha's Full Story:

Anusha, age 9, had changed schools numerous times as a result of an international upbringing, from southern England to Germany and recently to France, where she experienced bullying and was now in her second school there. Gentle, vivacious and enthusiastic about every sport and music activity offered to her, she presented with various behavioural challenges that seemed counter to her intrinsic demeanour and harmed the development of both her social and academic potential.

Her mother, a medical doctor, was loathe to medication and thus keen to try an alternative approach, while poised to present her for a psychiatric assessment. Her father had recently been diagnosed with ADHD, and Anusha exhibited mild autistic traits since infancy that she had so far pushed aside out of fear of stigmatisation, hoping that a ‘regular’ upbringing would resolve these. Anusha was fluent in French and English, relished the rural setting of her new hometown in southern France, and displayed an enchanting joy of life. Her first school experience there was overshadowed by meanness from her classmates, some of which might have been attributable to teachers actually hitting students, as the parents learned only after two terms. She was moved to a different school, where her performance was mediocre yet the environment more benign. Still, she was experiencing various difficulties, not integrating ideally, and appeared not to fulfil her true academic and social potential.

Anusha’s challenges presented as follows:

– sensory integration issues were noticeable since infancy. Anusha was sensitive to loud noises and rash movements. Music had to conform to her wishes and her parents were constantly aware of the acoustic environment in every situation, both at home and in public. She was also terrified of heights.

– social and executive functioning was deemed delayed, and partly ascribed to the frequent moves and sometimes hostile environment, as well as being an only child. Anusha had no concept of turn-taking, frequently interrupted in conversation while not showing awareness of social cues, and was not learning to work in teams. Playgroups she longed to join chose to ostracise her, repeatedly in each school and after-school setting.

– naturally energetic, she had trouble focussing on tasks and was easily distracted. Completing projects and assignments required supervision, and she often lost motivation, which reduced her self-confidence and willingness to persist, explore, take risks and explore

– when things didn’t go as she expected, Anusha would become impulsively aggressive, for example breaking her cello bow in frustration during a lesson. Practicing skills had to be supervised with patience and persistence, helping her sustain attention and maintain a positive outlook. She would become obstinate, ‘lose her rag’ and become aggressive when her idea of a planned activity did not materialise, and was relatively inflexible with regard to changes of plans, which took substantial negotiation and incentivisation to implement in the face of rebellion and emotional outbursts. Often, this aggression would turn into sustained rage, which she would find hard to calm down from.

– often anxious and nervous, with a heightened sense of hypervigilance, Anusha would self-stimulate from an early age, exercising mild repetitive habits for self-regulation, such as rocking in her seat.

Anusha came to the UK during term break for a one-week intensive neurofeedback training course. The prospect of watching her favourite movies all day was exciting for her, especially as her screen-time was strictly controlled.

We began with a brain map, while answering her questions as to what we were doing and looking to achieve. She was satisfied with the answers, understanding the rationale of helping her to maintain her calm, improve her persistence and focus, among other, and she volunteered examples of situations she would like to master better – this maturity and keenness to improve was impressive.

The brain map confirmed her vulnerabilities: A lack of sense of being part of something bigger, loner qualities or lack of understanding of social rules, social invasiveness, impulsive aggression and rage, distractibility and mood control issues, hypervigilance and hyperactivity, auditory hypersensitivity and fear, a recent betrayal (which she described), and a general sense of not feeling emotionally safe and being able to expand or unfold her potential. Structurally, her brain’s maturation was slightly behind age-matched peers.

We did twelve neurofeedback sessions in seven consecutive days, involving two sessions per day of two hours each, which she greatly enjoyed. Her parents took her swimming, shopping and to other touristic attractions during her lunch break and evenings, when she got to choose her favourite international foods. Already, her mother remarked that she found Anusha much easier to handle, and was surprised when she calmly accepted changes of plans when an outburst was expected. Her parents were able to visit friends and spend time together during her sessions, a welcome relief and vacation.

After a week of having returned to school, her parents noticed substantial positive changes in her behaviour. As her mother reported:

– She was definitely calmer and less explosive, not ‘losing her rag’ when parents were conditioned to expect this, something they had already noticed during the training week and a new behaviour that persisted

– spontaneously picked up a book and started reading, which was unheard of before; she took interest in illustrations, calmly sat in her favourite chair, and developed a passion for the story she was focussed on

– showed patience and persistence; for example, Anusha tried and completed difficult jig-saw puzzle, laughing when it became particularly hard

– demonstrated a healthy and rational assertiveness in many situations; she explained to her parents that she did not enjoy a certain after school activity and had only been doing it to please them

– had and improved interoception, or ability to understand and express her feelings, letting her parents into her realm of understanding how situations at school and interactions with peers made her feel. This was as if an invisible shield had been pierced, and both parents felt they bonded more closely with her and as a family

– successfully negotiated herself into a schoolyard playgroup which had previously been hostile towards her, which led to the prospect of sleep-overs and new friendships

– sensory integration issues resolved, no hypersensitivity to accoustic environment

– no noticeable anxiety / hypervigilance, nor self-stimulating behaviour, instead fully engaged in her environment.

A brain map at the end of the week confirmed these transformations. Encouragingly, her brain’s structural maturity metrics improved too, which was a positive surprise for such a short and intense training period.

Anusha’s mother had originally planned to make another trip to the UK during the summer vacation for further neurofeedback training. The psychiatric assessment a few months after her neurofeedback intensive found no grounds for an ASD nor ADHD diagnosis, and Anusha felt accepted and motivated in her school and after-school environments. The family went to Disneyland instead.