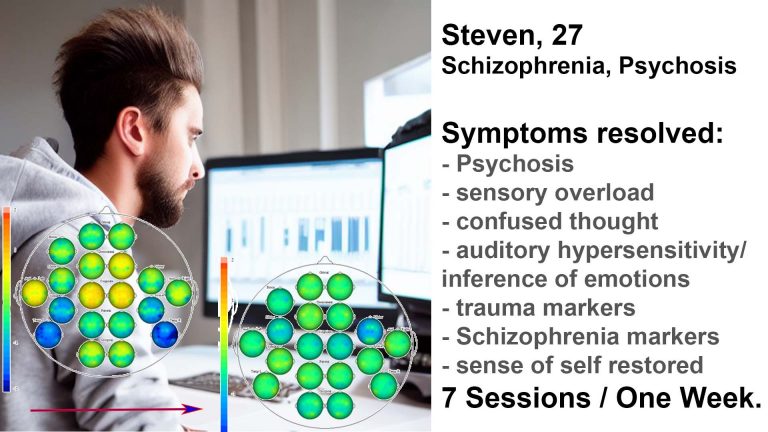

Case Study: Steven, 27, Schizophrenia, Psychosis

One Week Intensive Course as Launchpad to Independence

Before

– psychosis, including neuromarkers

– sensory overload

– relational, “centre-of-universe” thinking

– confused thought, delusions

– over-inferring emotional content into conversations

– schizophrenia marker

– various trauma markers

– impulsive aggression

– frequent clashes with his mother

– dependency on parents, living / working from home, social isolation

Seven Neurofeedback Sessions, One Week Intensive

After

– calmer, grounded, “I feel really good”

– purposeful, present, confident

– well-spoken, relevant, insightful conversations

– stable and less triggered

– flexible and more patient with his mother

– focussed, productive, launched business

– psychosis, schizophrenia and trauma markers resolved (!)

– open to different perspectives

Steven's Full Story:

Steven, 27, is a talented musician, artist and videographer. He has been creating content since his teenage years, and following college education got a job as a video editor for an independent advertising and production company, working from home. As a teenager, he had indulged in psychadelic drugs, which led to brief hospitalisations, being diagnosed with Schizophrenia and psychosis. Various medication attempts found chlozapine to be most effective, while Abilify did not work for him and he was able to stop using this. He was living on his own before lockdown, and while resenting the emotionally numbing side effects of his medication, as well as its physical impact, he continued to pursue his favourite sport, skateboarding, and personal music projects.

During lockdown, a combination of social isolation and an unsupervised attempt to reduce his medication resulted in another psychotic episode, forcing him to give up his independent lifestyle and move back in with his parents while temporarily giving up his job. Under psychiatric supervision, he was put on a higher dose of chlozapine, a frequent necessity among persons suspending its use. Working with a psychologist, he regained some stability and was able to resume his career. Living at home however intensified the conflict with his parents, in particular his mother, whom he deemed to be overly invasive and whose tone of speech and mannerisms frequently triggered him. Combined with his lost independence and higher medication dosage, his self-confidence suffered as he saw himself regressing.

His mother, a medical doctor, took an interest in neurofeedback and brought him to London for an intensive training course.

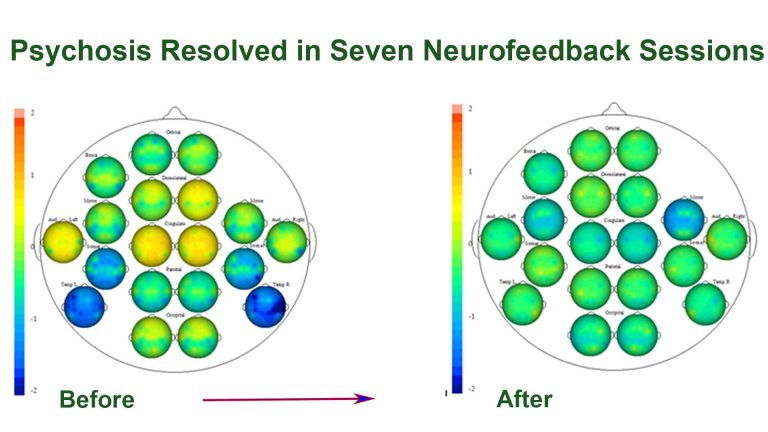

In only seven sessions, we were able to stabilise brain function by eliminating crucial psychosis and trauma markers, with the result evidenced in his brain map below (orange areas are dysrythmic, and green the desired state). He watched movies of his choice, and was able to handle 2-3h sessions with substantial self-discipline, as the medication and jet-lag made him prone to sleepiness as soon as he relaxed. We alternated movie content between Sci-Fi and comedy to cater for his attention cycles. After the third session he remarked, “I’m not sure if it’s the placebo effect, but I feel really good”, meaning calm, grounded and deeply content. While the training at times required a physical effort to stay awake and focussed, he felt refreshed and at peace after each session. Exploring a new environment – London – in between sessions provided further motivation and joy.

His mother was somewhat disoriented by his change in demeanor; she was worried that he was not pursuing his hobby of photography during the times they explored the city of London together. He explained to her that he was enjoying the moment, and found himself less triggered by her emotional responses. Changes were happening, quickly and substantially; cognitively, this manifested in a new sense of calm, groundedness and self-confidence. Sensory overload, auditory sensitivity and thought confusion were substantially reduced. The changes were apparent in his composure, and to me as the practitioner, it felt as though there was a new, mature and content person before me.

We had trained his Default Mode Network, as well as brain areas responsible for trauma symptoms. A brain map confirmed that he had responded incredibly well, and changes in functional activity were real. We had shown his brain what it feels like when the relevant brain areas ‘behave’, or show less dysrhythmia, and enjoyed the result.

To consolidate the training effects, he focused on his work, resumed sports and a healthy lifestyle, and made a new effort at resuming social contacts and integration. Still living at home, the frequency of outbreaks caused by being triggered by his mother reduced significantly, though there were still situations where they clashed. Steven had gained a new sense of interoception, understanding when he was feeling unstable and what aspects of his physical and social environment contributed towards this. He drew on conversations he had had with his psychologist to make conscious efforts at avoiding these triggers, and decided he did not want to pursue talk therapy.

Feeling more emotionally present, he found that social events could trigger an awareness that his life had been hijacked by his condition, and that he was missing out on developments ‘normal’ people go through. He was also still living at home in the outer suburbs. His mother, meanwhile, was frustrated that there were still incidents where they clashed. Unfortunately, she found it difficult to understand that some of her behaviour, such as excessive invasiveness, changes in her tone of speech when becoming emotional, a tendency to blame everything and everyone apart from herself, mood instability, a lack of social integration and unattainable expectations regarding her only child. Particularly worrying was her tendency to view, and talk about, Steven has ‘having a disease’. Somehow, in her mind, this exonerated her and relieved her of the need to work on herself. Ideally, she could have done neurofeedback training herself, which would have addressed some borderline tendencies.

Still, conversations with a therapist who understood both provided some important mediation, and raised the prospect of letting Steven pursue his dream of independent living again. A year later, Steven has moved to the City and has launched his own photography business, separate from his flexible day job.

As an aside, it was interesting to note the absence of Steven’s father in this process. A gentle person, he was removed from outbursts yet also appeared to play no role in calming situations or guidance. This was visible on the brain map, and an important brain area to focus training on.

The speed with which this transitioned in Steven is remarkable. We find that when we resolve psychosis (which has prominent neuromarkers), a person’s new brain map can show a substantially different picture. Technically, this corresponds to the phenomenon where the cingulates dominate cortical functioning during psychosis, and a ‘relief’ shows us the underlying character. In Steven’s case, this was relatively well-matured, and the brain area responsible for his perceived thought disorder responded well to intensive training, in essence embracing a more grounded mode of functioning.